Exploring LA’s Water Legacy in the Owens Valley

When you turn on the tap, do you know where your drinking water comes from?

The typical Angeleno has no idea that the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power imports nearly a third of its water from the distant Owens Valley, known by the indigenous Paiute people as Payahuunadü, “The Land of the Flowing Water.”

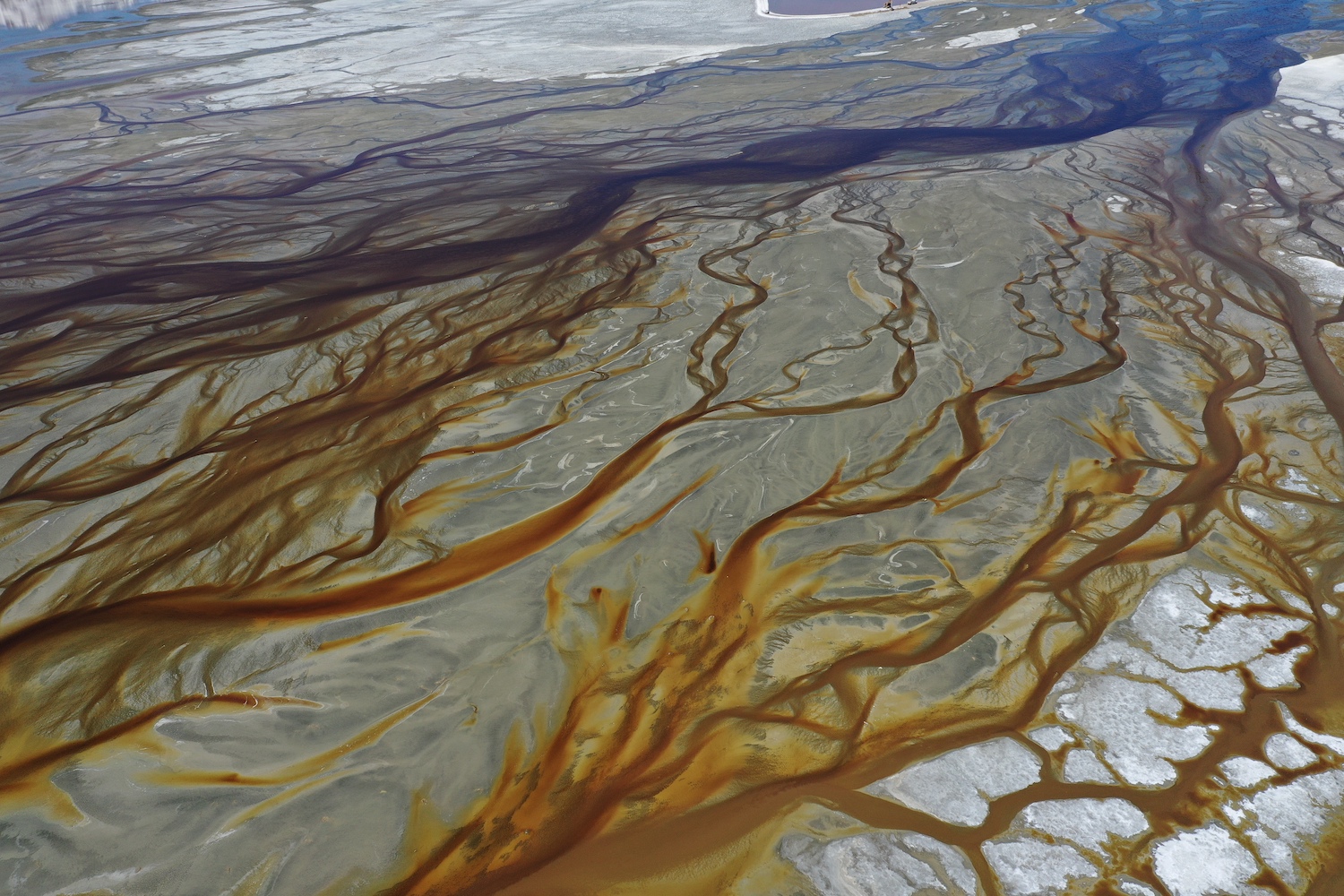

This water (paya) comes through the LA Aqueduct, which diverts Eastern Sierra snowmelt from the Owens River and Owens Lake. Payahuunadü once served as an oasis with plentiful water supplies. The Paiute people (Nüümü) lived off the land, aided by irrigation channels that spread water throughout the valley.

Within a short time period, the City of Los Angeles drastically reshaped the area with a gravity fed water conveyance system hailed as an engineering miracle when it launched in 1913.

But that 233-mile network of channels and conduits had devastating repercussions for the people and the environment that continue to this day. It essentially eliminated the once-thriving Owens Valley ecosystem and any viable farming.

This stark reality was brought into sharp focus for Heal the Bay’s science, policy, and outreach team during a recent trip to the Owens Valley. To better understand L.A.’s checkered relationship with water, seven staff members attended a two-day Walk of Resilience and Accountability hosted by Walking Water, a nonprofit aiming to restore our relationships with water, lands, and people.

In the coming weeks, we will share more details of our journey and staff reflections on how to better secure L.A.’s water future while repairing the harm done to the Owens Valley and its people.

The LA Aqueduct brought water to greater LA in response to continued urbanization and growth of the city in the late 1800s and early 1900s. William Mulholland and the city agency he led, which would become LADWP, looked to the north for new sources of water for thirsty LA.

At opening ceremonies for the Aqueduct, Mulholland famously (and problematically) said of the diverted water: “There it is, take it.” LADWP had bought up property in the Owens Valley, parcel by parcel, posing as ranchers and farmers, to acquire water rights. The movie Chinatown is loosely based on this true story.

Within approximately 10 years, the Aqueduct had completely drained Owens Lake (Patsiata), resulting in the loss of navigable waters, habitat, and an important local food source. The dry lakebed became a major source of dust pollution. Owens Lake has been named as the largest source of dust (specifically PM10) in the U.S., according to the USEPA.

The diversions had and continue to have major detrimental impacts to the environment, people, and wildlife of the Owens Valley. Harmful metals left in the dry lakebed blow across the Valley, causing a slew of breathing problems and other harms to many local residents. Without abundant water, the Paiute people lost their economic livelihood and way of life.

Lawsuits and regulations led to required mitigation for the dust by LADWP, which began the largest dust control project in the nation in the early 2000s. Dust mitigation involves physical alteration of the drained lakebed, irrigation with sprinklers, and planting to keep the dust in place.

During our tour, Heal the Bay connected with staff from the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, local tribes, and allies. We walked, learned, reflected, and connected with water and each other.

We trekked down into and around Patsiata and visited the Three Creeks Collective — land that has been given back to indigenous tribes through the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission and the Collective.

The trip was humbling and transformational for those who attended. We felt incredible gratitude for the experience and to the local indigenous elders and community members and allies for welcoming us so openly.

We heard numerous requests and demands of local agencies, the main one being to the return of local water rights to Payahuunadü.

The City of Los Angeles has grown because of the decisions of the past to divert water from Owens Valley. Nearly 4 million people and a robust economy depend on that water.

Untangling from that water supply will require significantly reduced water demand, innovative planning, and billions of dollars for new water supply and storage infrastructure.

Heal the Bay, and others are actively pushing greater LA to become more water-independent through increased stormwater capture and wastewater recycling. And that will require both higher rates on local water bills and increased infrastructure investment by government agencies. All of these factors affect civic and individual pocketbooks.

Without low-income rate assistance, burdens for these investments will be placed on communities already struggling to pay for their basic needs. Balancing all these competing interests will require great care, diplomacy, and collaboration. Heal the Bay is committed to leading these policy discussions with respect for all interested parties and with science-based recommendations.

We must prioritize truly local water. We can no longer justify diversions from Owens Valley. The ecosystem and environmental justice harms created by the Los Angeles Aqueduct should be rectified by leaving more or all of the water in Payahuunadü and mitigating for past and current impacts.

Here are some great resources to help you get involved in this issue:

Learn More

Websites: The Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, The Three Creeks Collective

Visit: Owens Valley Paiute Shoshone Cultural Center

Watch: Paya – The Water Story of the Paiute (only available on DVD), The Aqueduct Between Us

Provide Financial Support

Donate financially to the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission

Walk the Land

The next Walks of Resilience and Accountability will be in Los Angeles Oct. 24-26. Register here.

Register for the ongoing virtual Water Learning Series.

Stay tuned: In our next installment, Heal the Bay staffers will share eyewitness accounts of their walking journey.