Solving Mystery of the Disappearing Sea Stars

Staff Scientist Dana Roeber Murray says a newly identified virus has wiped out millions of sea stars in California.

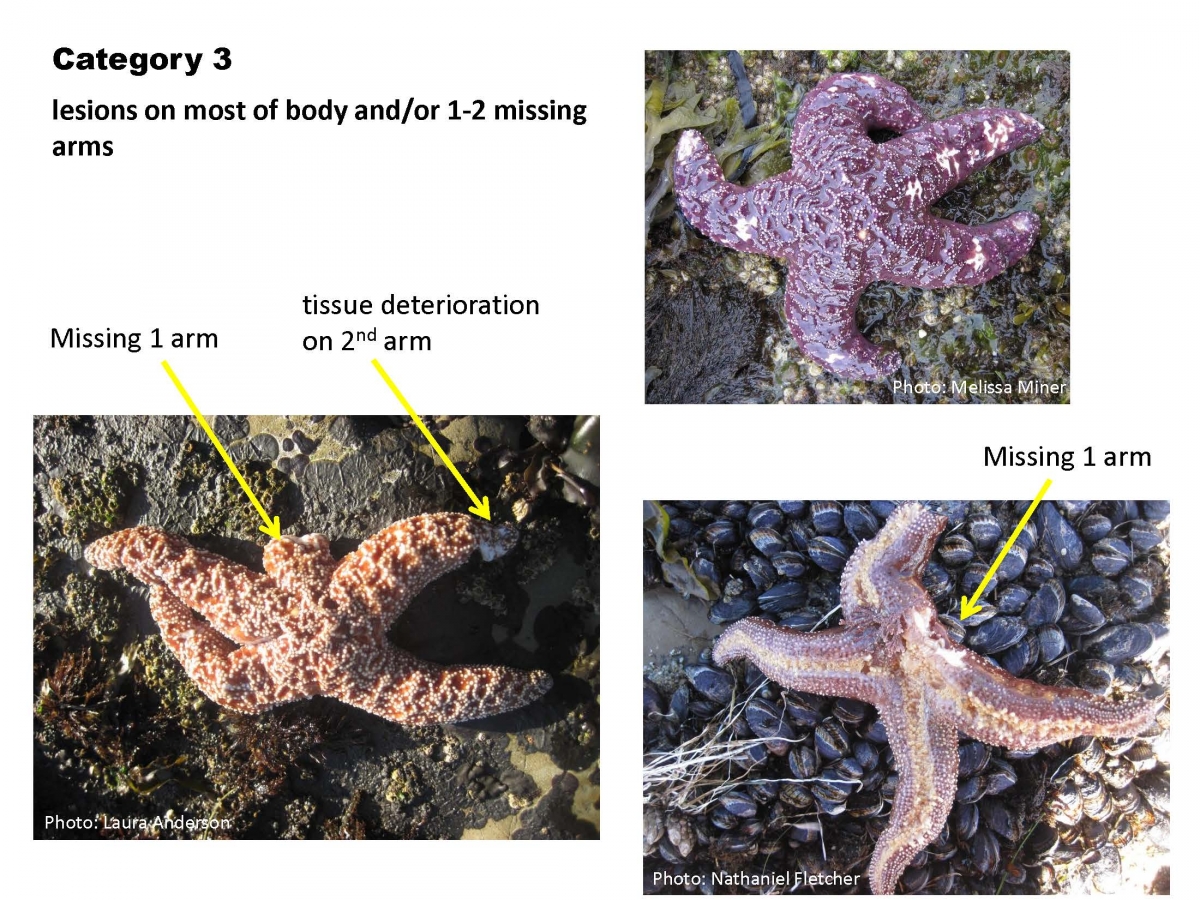

Where have all our sea stars gone? Once abundant in our tidepools and rocky reefs, millions of sea stars have wasted away and disappeared along our coast. Just last weekend as I went tidepool exploring at Leo Carrillo State Beach during a minus tide, we encountered octopuses, sea hares, urchins, and little fish — but not a single sea star. This time last year, the scene included missing limbs … melting masses of flesh … gooey lesions overtaking the entire body. Divers and tidepoolers encountered numerous sea stars with white lesions that eventually decomposed body tissue into a goo-like blob.

Over the past year, an international team of scientists worked together to get to the bottom of the mysterious marine infectious disease wiping out our sea stars. Just this week scientists have identified the pathogen responsible for the West Coast sea star die-off, through research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Scientists say that the virus is different from all other known viruses infecting marine animals, and they’ve named it “sea star associated densovirus.” The progression of symptoms can be very rapid, with initial signs leading to death within a few days. Figuring out marine diseases and identifying what virus is to blame is difficult because one drop of seawater can contain 10 million viruses. Researchers had to sort through millions of marine viruses to identify the culprit.

The identified densovirus weakens the sea star’s immune system, making it more susceptible to bacterial infections, such as sea star wasting disease, a fast-moving scourge that has occurred along our coast for decades, but not at the recent widespread level. Reports of disintegrating sea stars have come from as far north as Anchorage, Alaska, to our shores along Palos Verdes, and down south to La Jolla. The current epidemic began in Washington in June 2013; since then at least 12 different species of sea stars and even some purple sea urchins have been found as victims. By the fall of 2013, the disease had become widespread along the Pacific coast.

Sea stars, in particular ochre stars, are an important keystone species that have the potential to dramatically alter rocky intertidal community composition. Removal of this top predator from intertidal ecosystems can affect the whole food chain. After past wasting events, ochre stars were absent along Southern California’s shoreline for years.

Going forward, scientists will be observing the next generation of baby sea stars that are starting to show up along some Pacific Coast beaches. “We are interested in the potential for stars to develop resistance to this outbreak,” says Drew Harvell, a marine epidemiologist at Cornell University and the University of Washington who has been coordinating the research. “The only way forward and to have sea stars in the future is for them to develop resistance and having new stars to propagate.”

Leading scientists continue to investigate environmental factors that may have caused sea stars to be more susceptible to viral infections. Those factors include effects from climate change such as warming ocean waters and ocean acidification. Important to note, there is no evidence at all that links the current wasting event to the ongoing disaster at the Fukushima nuclear facility in Japan.

Scientists ask the public to keep an eye out for infected sea stars and urchins. If you see any possible infections while out in our local intertidal and subtidal seas, please report your findings to seastarwasting.org.