Sniffing Out the Truth About Orca Poop

Sheila McSherry, Heal the Bay’s Foundation Grants Manager, has a whale of a time looking for scat in the Pacific.

Through a friend’s invitation, I recently got the chance of a lifetime — hunting for whale excrement on the open sea! It may sound icky and a bit strange, but it’s not. It’s actually an important step in the fight to protect the gentle giants of the deep.

I joined the Center for Conservation Biology and Conservation Canines, a nonprofit organization based out of the University of Washington, on a recent orca whale research trip near the San Juan Islands. As its name indicates, the center uses dogs to help collect whale fecal samples to determine the health status of the region’s Southern Resident Killer Whales.

As a longtime fundraiser for Heal the Bay, this outing on the water let me leave my laptop and deadlines behind and reconnect with the marine life we work so hard to protect. I also got to play scientist for the day!

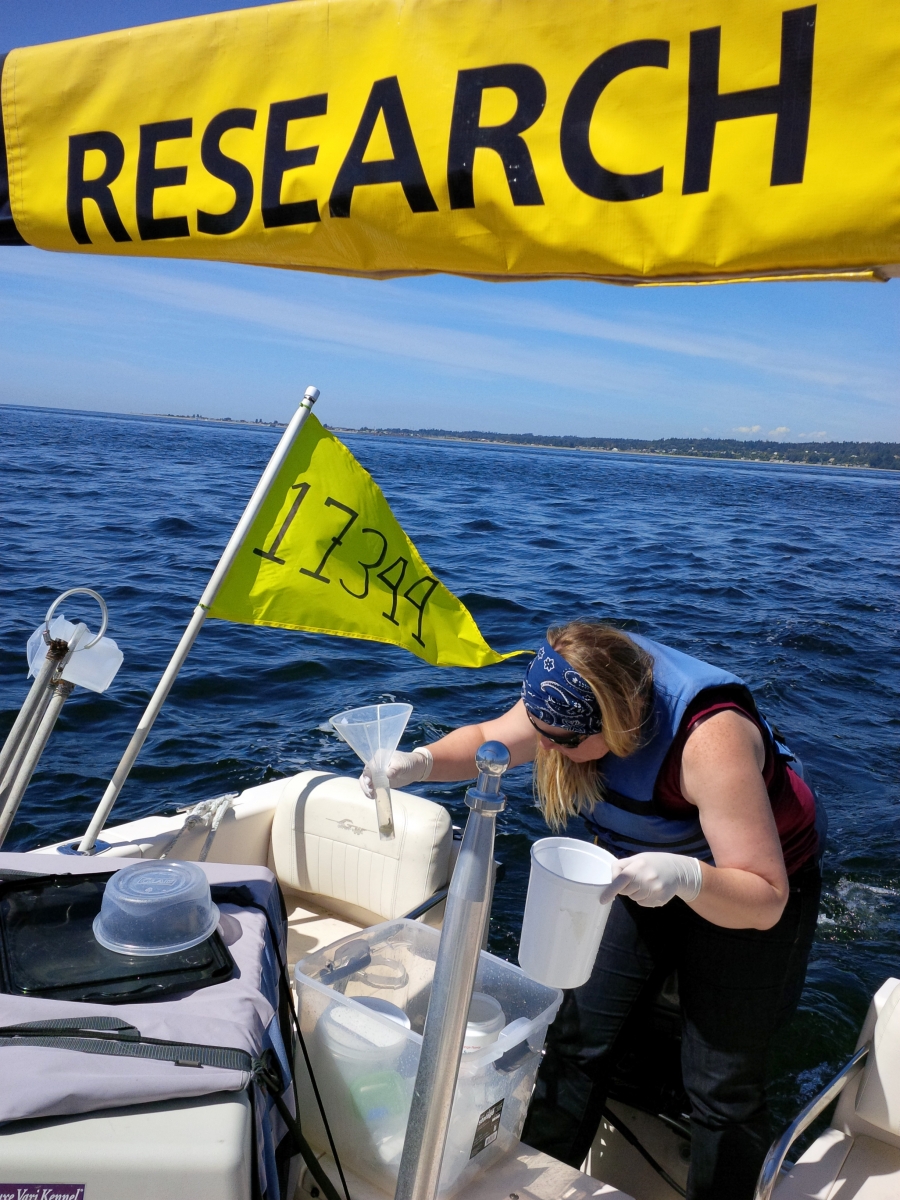

On a sunny morning, I joined a crew that spent the day followed the orca whales around the islands and to the Strait of Georgia aboard the research vessel Moja. My fellow passengers included Dr. Deborah Giles, a marine biologist who collects orca whale behavior data to assess the effects of decreased prey availability and noise pollution on the animals; wildlife biologist Elizabeth Seely; and a seafaring dog named, Tucker. I was so mesmerized by the beauty and power of the foraging and breaching orca whales, I nearly forgot we had a job to do!

Tucker, an energetic black Lab scat detection dog, was the chief detective. As Seely steadied him, Tucker leaned over the bow of the boat and communicated through movements and sounds when he sniffed a sample. Giles then maneuvered the boat so that it was easier for us to collect the samples using a clear beaker attached to the end of a long pole. These samples are sometimes as small as a lentil and can sink quickly in the open ocean. So we moved quickly to grab samples, which are tested for DNA, stress hormone levels, diet, the nutritional status of the whale, and toxins like DDT).

Conservation Canines employs rescue dogs to do its work. Tucker was found undernourished and wandering the streets of North Seattle by ShoLine Animal Shelter before becoming a scat detection dog. What makes him even more remarkable is that he is the only dog in the world trained to detect killer whale “scat” in the open ocean. His reward when he finds a sample? A rousing game of catch with his favorite WestPaw ball.

There are three resident killer whale populations found between Washington state and Alaska. These whales are called residents because they spend about half of the year foraging in inland waters, and rely almost exclusively on salmon as prey. The Southern Resident Killer Whales are the most threatened, with a current population of 78 animals.

There are three hypotheses that have been proposed for their decline:

- Less access to the whales’ primary prey, Chinook salmon

- A disturbance from private and commercial whale watching vessels

- Exposure to high levels of toxicants (e.g. PCB, PBDE and DDT), which are stored in the whales’ fat.

Understanding the relative impacts of these three pressures is vital to mitigating further whale losses.

Joining Conservation Canines for the day is an experience I will never forget. And as I move in to my ninth year in environmental fundraising, I’m feeling energized by all of the promising research and advocacy to protect endangered marine life here in the Santa Monica Bay and beyond. The Pacific Ocean is connected to us all. So it’s gratifying to know Tucker is doing his part, while I do mine in an office in Santa Monica.