The Raw Truth: The Real Deal About Sewage Spills

What caused last month’s sewage spill in the Bay?

Over 30,000 gallons of raw sewage discharged unintentionally into Ballona Creek and then into the ocean on May 8-9. The spill forced full closures along Dockweiler Beach and Venice Beach, two of the most popular shoreline spots in greater L.A.

The culprit was root blockage in a main sewer line in West Hollywood. Over time, tree roots can infiltrate sewer pipes causing them to clog or break. A sewer main is a publicly owned pipeline, typically located under a street, that collects waste from numerous homes and businesses and transports it to a wastewater treatment facility. Based on the spill report from the State Office of Emergency Services, it appears that the sewage blocked up in West Hollywood, spilled onto the street, and entered a storm drain, which eventually made its way to Ballona Creek and out to the ocean.

How much icky stuff reached the sea?

According to the most report from California Integrated Water Quality System Project (CIWQS), it was revealed that a staggering 31,763 gallons of sewage were discharged from this residence, significantly surpassing the initial estimate of 14,400 gallons, which was the amount widely reported in the media.

What damage can these spills do to humans and the ecosystem?

Raw sewage is very dangerous to people and wildlife, as it contains bacteria, viruses, and can carry a variety of diseases. There is also debris in raw sewage, such as wipes, tampons and other personal health items. When released into waterways and the ocean, the waste and debris can harbor bacteria or be ingested by animals. Sewage is made up primarily of organic matter that is food for smaller organisms at the bottom of the food chain like algae. A large discharge of sewage can lead to algal blooms that can deplete oxygen in the water, possibly leading to fish kills and impacts to aquatic organisms and ecosystems. Discharges of sewage can also increase the cloudiness of water, smothering species or impacting the amount of light that can pass through the water for photosynthetic organisms.

Did some media overplay this story?

A recent Los Angeles Magazine article “Beach Residents are Sick of the Crap”, made a link between the recent sewage spill from Ballona Creek and reports of “dead fish and birds” and sick surfers in the area. Heal the Bay takes sewage spills and threats to public and environmental health very seriously. But we pride ourselves on being a science-based organization and we question whether this assertion is backed up with robust data. It is tempting to use anecdotal evidence to indicate causation, but to effect change we must rely on good data to back up our advocacy. Recently there have been increased reports of starving and sick pelicans, but these reports preceded the latest sewage spill. We don’t have enough evidence to conclude that the impacts on fish and birds are related to sewage spills. Researchers and advocates must continue to identify the reasons why pelicans are starving while also working to stop sewage spills and protect public health.

Heal the Bay got its start nearly 40 years ago by making sure raw sewage didn’t get released into local waters. Why do we still see these discharges happen?

Heal the Bay’s first fight was to stop partially treated sewage from being discharged into the Santa Monica Bay from the Hyperion Wastewater Treatment Plant. Hyperion now treats wastewater to a much higher degree and, when everything functions properly, we actually aren’t concerned about bacteria or viruses being discharged into the ocean. But climate change is already impacting our sewer systems; as we see more intense storms, some of that water is finding its way into sewer pipes, scouring the debris that gets stuck in our pipes, mostly wipes, which can overwhelm our treatment plants. Hyperion isn’t designed for these intense storm events, and in fact, hasn’t had a major overhaul since Heal the Bay pushed them to 40-years ago. We have other concerns about treatment plants too — like the discharge of treated water, which can be recycled and reused, and the discharge of nutrients into the ocean, which is exacerbating impacts of ocean acidification and warming. And we know that major spills from treatment plants can and do still happen, like we saw in 2021 at Hyperion.

Spills that happen outside of treatment plants from sewer pipelines are often due to aging infrastructure. Pipes don’t last forever and maintenance and replacement are required. According to a statement that Director and General Manager of LA Sanitation & Environment Barbara Romero gave to Los Angeles City Council, approximately one-third of the city’s pipelines have exceeded the 90-year mark. Typically, sewer pipes are designed with a lifespan ranging from 50 to 100 years. Given that the majority of Los Angeles’ sewer infrastructure predates 1950, it’s evident that a significant portion is approaching the end of its operational lifespan. As a region, we must invest in and prioritize infrastructure repair and replacement. That will likely mean higher utility rates. As we make repairs, we must also be forward-thinking of the current changing climate and what’s to come, planning for opportunities to maximize water recycling and readying for larger and more intense but less frequent rainfall.

Was this a one-off event or should we be worried about an increased amount of spills in the future?

Unfortunately, discharges happen periodically but they vary widely in volume and whether the sewage actually reaches a waterway – namely a river or the ocean.

Major sewage spills are fairly rare, but we have had some big ones in the last three years. In July 2021, Hyperion had a major failure and discharged 12.5 million gallons of sewage to the ocean from its outfall pipe that discharges one mile into the ocean. The proposed fine of $27 million by the Water Board is still being negotiated by the City of LA. In December 2021, 8.5 million gallons of sewage was discharged into the Dominguez Channel from an overflow in an LA County Sanitation Districts pipeline. LA County paid a fine of $6 million for this spill and 14 others, with much of the fine returning to fund a local stormwater park to benefit the community. The LA Magazine article incorrectly attributed this spill to the City of LA, when in fact it was the County of LA.

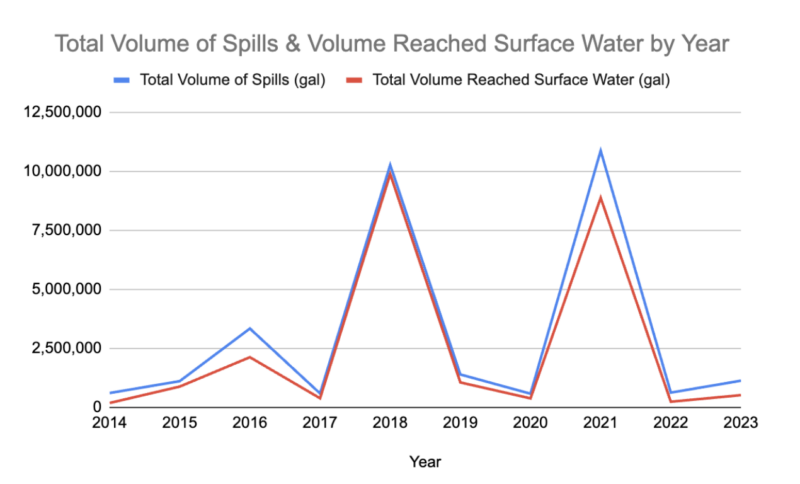

However, smaller sewage spills are not an uncommon occurrence regionally. Sewage spills are tracked by the state which is where Heal the Bay pulls data to look at trends over time. Over the last 10 years (2014-2023), there have been a total of 3,174 spill cases resulting in 30,521,025 gallons of sewage in LA County, with around half of that amount reaching surface waters.

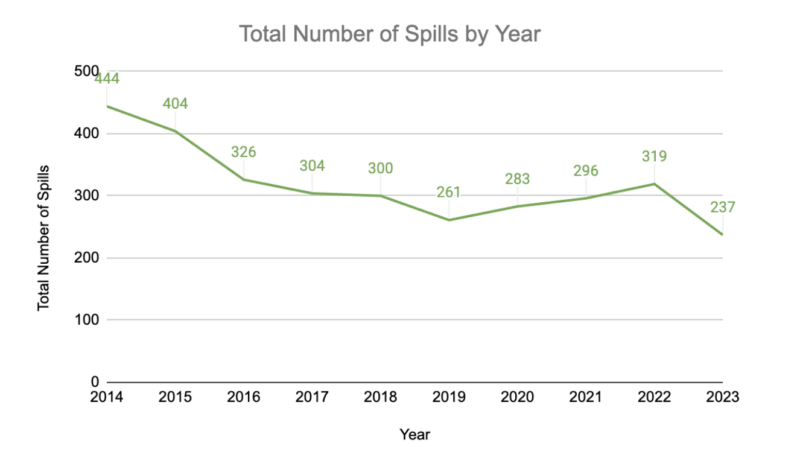

The number of spills actually shows a decreasing trend over the last 10 years (see chart below), but there is not a clear trend when we look at volume spilled over time. Clearly, we see spikes in years when there were major spills. Obtaining data on spills is not easy or user-friendly and the data itself is not perfect. The graphs below actually don’t have the 2021 Hyperion spill in them due to that data being listed differently by agencies.

What’s the difference between sewers and storm drains?

We must remember not to confuse the sewer and storm drain systems, which are separate in Los Angeles. Waste from inside homes and businesses enters the sewer system and is treated before being discharged into the sea. Meanwhile, rain and daily urban runoff (sprinklers, hosing down sidewalks, washing a car in the street) enters our storm drain system. That daily runoff, which can amount to 10 million gallons in greater LA even on a dry day, is not cleaned and enters waterways and the ocean directly.

The LA Magazine article conflates the two, describing “pools of raw sewage [that] puddle in heavily traveled areas, like the beach in front of Santa Monica’s Shutters and Casa del Mar hotels.” These two hotels sit near the outfall of the Pico-Kenter storm drain, which drains major portions of Los Angeles and Santa Monica. During storms, Pico-Kenter funnels huge amounts of trash and toxins to the beach and ocean. The puddles described by LA Mag were very unlikely to be raw sewage and much more likely to be stormwater runoff, which is typically filled with unsightly trash and bacteria which can cause illness but is less of a health concern than raw sewage.

Who is responsible for maintaining the sewer system?

The sewer system in LA County consists of 17,000 miles of pipes and is both publicly and privately owned.

Lateral lines are privately owned and connect homes and businesses to the public system. Homeowners and business owners are responsible for maintaining and cleaning those lines, which are known to get clogged and impacted from tree roots. Regular maintenance is key to preventing problems and sewage leaks and spills from lateral lines. Blockages can also be prevented by all of us by not flushing anything down the toilet except toilet paper and waste. That means no wipes (even if they’re flushable), tampons, condoms, plastic, needles, or anything else. And for sinks, that means no fats, oils, and grease, which can clog pipes as well.

LA County Sanitation Districts’ service area covers 78 cities and the unincorporated areas within the County (824 square miles); the City of LA is responsible for more than 6,700 miles of sewers. Finally, the wastewater ends up at wastewater treatment or water reclamation plants.

The City of LA operates four plants: Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant, Los Angeles Glendale Water Reclamation Plant, Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant, and Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant. The County of LA operates 11 wastewater treatment facilities, the largest being the A.K. Warren Water Resource Facility (formerly known as Joint Water Pollution Control Plant) in Carson.

Are the various agencies and municipalities doing all that they can to prevent these spills?

The City and County of LA recognize the need for maintenance, upgrades, and replacement of aging infrastructure. Staff is also focused on improving systems and processes for detecting, responding to, and notifying the public of spills.

Heal the Bay and our partner non-profit organizations meet regularly with leadership at LA County Sanitation Districts and we appreciate their transparency as well taking accountability for spills and reinvesting in local communities. The scale of the problem for LA City and LA County is huge in terms of identifying and prioritizing areas in need of repair across 17,000 miles of sewer pipes.

What is Heal the Bay doing to make sure these spills don’t happen in the future? How are you holding dischargers accountable?

Heal the Bay is dedicated to protecting public health and making sure that spills don’t happen in the future by:

- Advocating for:

- Increased transparency and commitments from LASAN and LACSD as well as the Department of Public Health on coordination, rapid testing, and rapid notification of the public when there is a sewage spill, especially major ones that could have an impact on public health.

- Appropriate fines when there are spills and requiring those fines to be invested in local communities that were impacted and water quality improvement projects

- Funding for City and County of LA to make necessary upgrades to infrastructure through local, state, and federal funding as well as through rate increases

- Heal the Bay supports the recently proposed sewer rate increases by LA Bureau of Sanitation & Environment as it must address aging infrastructure and keep up with inflation, the agency’s needs, and our new climate reality.

- Implementation of the recommendations in the report from the 2021 sewage spill at Hyperion

- Educating residents on actions they can take to prevent sewage clogs and spills.

- Informing the public when there is a spill as a trusted voice in the community through our social media, blogs, and the Beach Report Card and River Report Card.

How can residents support those efforts?

- If you’re a homeowner or business owner, maintain your lateral sewer lines.

- Prevent clogs and spills by educating yourself, your family, and friends on what is ok or not ok to flush down the toilet and don’t put fats, oils, and grease down the sink.

- Support Heal the Bay’s advocacy work by donating or sponsoring our Beach Report Card.