Today’s guest blogger is Dana Roeber Murray, a Heal the Bay staff scientist who works on coastal resource protection issues.

Cold, salty water hits my face as I begin to breathe through my regulator – tiny bubbles floating up to the surface as I exhale. As I descend, light filters through the amber-hued blades of kelp as a school of golden señoritas swim past me near Big Kelp Reef in Point Dume. Once I am hovering above the ocean floor, neutrally buoyant at about 40 feet, my neoprene-wrapped body has adjusted to the chilly water and I snugly affix the end of my transect line to the top of a giant kelp holdfast. Data sheet and dive slate in one hand, transect line and flashlight in the other, I give a nod to my dive buddy, consult my compass and begin to swim at a 180-degree heading.

We’re conducting research for Reef Check, which provides data to state marine managers to make informed decisions about Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). The data we collect is used to assess the health of rocky reefs along the California coast, from species abundance and diversity to the sizes of individual fish.

I’ve been involved in scientific diving since 2003, and have logged hundreds of surveys underwater. I am excited to continue researching our local reefs once the new network of MPAs take effect in Southern California on Jan. 1. MPAs are essentially underwater parks in biologically important areas of the sea, where marine life can thrive because they are protected from consumptive pressures. The data we collect will be used to compare marine life inside and outside MPAs, and contribute to the ongoing, adaptive management of these MPAs.

Back in Point Dume, a bright orange garibaldi, California’s state marine fish, curiously peeks out from a rock cave. I estimate its size and make a note on my datasheet. A school of shimmery purple blacksmith envelops me and I count dozens of fish in seconds as they swim by me. Taking hold of my flashlight, I illuminate the underside of a rock ledge – prime territory for a brightly-striped treefish or a snoozing horn shark. Instead, I find a pair of active antennae attached to a vividly-colored red spiny lobster. I make a mental note that there are lobster to find along the transect line when I survey invertebrates on the way back. After about 10 minutes of searching, identifying, counting and sizing, I’ve completed my first fish survey of the dive.

I go on to complete two more surveys – locating beautiful chestnut cowries and spiky red urchins along my invertebrate transect, and recording the myriad of algae species along my seaweed survey. After signaling my dive buddy, we ascend slowly to the surface, completed data sheets in hand. Once we break the surface, we chat enthusiastically with other scientific divers about the fascinating animals. “Did you see that long sevengill shark?” “You wouldn’t believe how big that purple sunflower star was!” “I found three abalones on my survey!”

While contributing to marine conservation, volunteer divers benefit through friendships forged with other like-minded divers, amazing underwater experiences, and learning first-hand about our unique kelp forest and rocky reef ecosystems. If you’re a diver, and want to get trained to collect underwater data on MPAs, get involved with Reef Check.

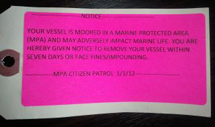

Non-divers can help on land by registering as a citizen scientist with Heal the Bay’s MPA Watch program.

Come join us.