As the nation takes stock on this Giving Tuesday, think about what the Bay means to you and your family. We can’t take our region’s greatest resource for granted. If you’re not already a supporter, please make this the day to donate to Heal the Bay, the longest-serving watchdog for Southern California’s beaches and ocean.

For a $35 donation, you can become a member of Heal the Bay and take pride in protecting what you love. The ocean belongs to all of us, and it’s up to all of us to care for it. It’s a great day to join us!

It may be Giving Tuesday, but consider what our local beaches and ocean give to us every day of the year:

- Sustenance The ocean provides 70% of the world’s oxygen. Santa Monica Bay, home to thousands of marine species, is part of an amazing local ecosystem.

- Prosperity Nearly 400,000 jobs in Los Angeles County are ocean-related, responsible for $10 billion annually in wages and $20 billion in goods and services.

- Connection We are all linked to the sea via L.A.’s network of watersheds. A day on the beach binds us together, regardless of our background.

Yes, Black Friday, Cyber Monday and Giving Tuesday began as marketing gimmicks. But the reality is that December is a critical month for us. Nearly 70% of private donations to Heal the Bay are made in the final two months of the year.

Private donors fund our annual operating budget. With recent cutbacks in government funding, contributions from individual donors like you are critical for maintaining proven and effective programs that keep our shorelines clean, healthy and safe.

As the year-end holidays approach, our local waters face a number of threats – from oil drilling off Hermosa Beach to a proposed string of desalination plants along the California coastline. Your gift today will help us hit the ground running next year and stand up for the bay we all love.

Heal the Bay staff is all smiles after a tour of the Hyperion plant, the historic Ground Zero for the group.

Heal the Bay staff is all smiles after a tour of the Hyperion plant, the historic Ground Zero for the group.

Visitors enjoying the open space afforded by the Ahmanson Ranch purchase in 2003.

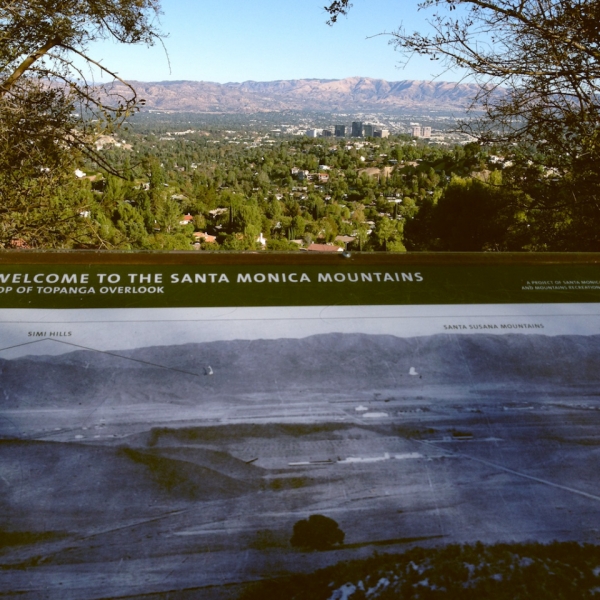

Visitors enjoying the open space afforded by the Ahmanson Ranch purchase in 2003. Signage at the Topanga Overlook.

Signage at the Topanga Overlook. Black perch congregate in MPA off Catalina Island

Black perch congregate in MPA off Catalina Island