Feb. 22, 2016 — Most people have no idea there’s a plan afoot to build L.A.’s first desal plant. Staff scientist Steven Johnson reports on building opposition to the proposal.

Want to know where the real action is in Manhattan Beach on a Tuesday night? Hint: It’s not popular bars like Shellback or Sharkeez. No, the real hot spot is the Manhattan Beach City Hall. It’s where you could find me and my Heal the Bay wingman Jose Bacallao last Tuesday night, speaking out against the building of an ill-advised desalination plant on the South Bay shoreline.

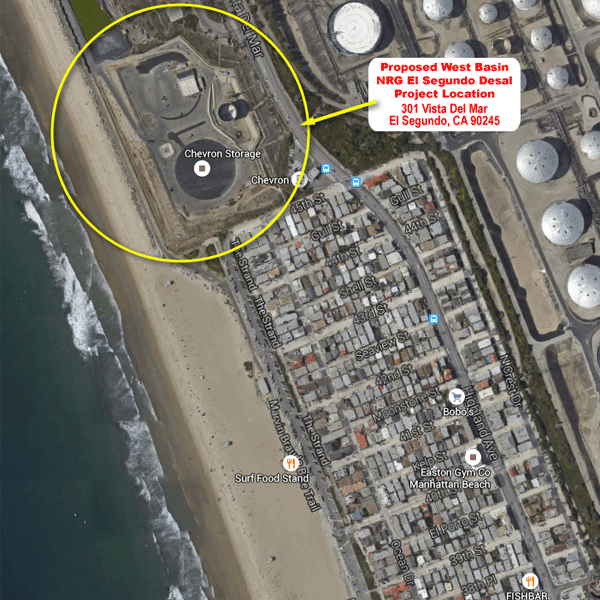

Very few Angelenos – let alone Manhattanites – have any idea that the West Basin Municipal Water District wants to construct a massive desalination plant on the beach near the El Segundo-Manhattan Beach border. The district hopes to release in June its Environmental Impact Report for the project, which would be the first full-fledged desal plant in Los Angeles County.

While we are waiting to see the analysis within the EIR, Heal the Bay has concerns that this is simply the wrong project, at the wrong time, in the wrong place. The $300 million plant aims to convert up to 60 million gallons of seawater a day into drinking water for the 17 cities the agency serves.

Besides our obvious concerns about the plant literally sucking the life out of the ocean, we worry about West Basin wasting a lot of time, energy and ratepayer money.

Why build a costly desal plant before fully exploring more efficient infrastructure options like water recycling and stormwater capture?

Though the EIR isn’t due until June, the council put the discussion item about the proposed plant on the agenda to begin formal public discourse about the sure-to-be controversial project. You’d expect Heal the Bay to be worried about desalination, but some other powerful opponents to the proposed project also lent their voice to the debate Tuesday night.

Manhattan Beach Mayor Mark Burton described the proposed plant as “a giant step backward in our commitment to getting the Santa Monica Bay back to its natural state.” Hermosa Beach Mayor Pro Tem Hany Fangary also lent his voice of dissent. Craig Cadwallader, a longtime Heal the Bay ally and driving force at the South Bay chapter of the Surfrider Foundation, also urged West Basin to more fully explore recycling infrastructure before embarking on a costly desal plan.

Bacallao, the senior aquarist at our Santa Monica Bay Aquarium, and I spoke during public comments. We reminded attendees that ocean desalination is bad for the wallet, marine life, and the future of our coastlines.

After spirited discussion, the Manhattan Beach City Council voted 5-0 to approve a letter to West Basin Municipal Water District opposing the project and listing the city’s specific objections.

The action is largely symbolic, as council does not have any regulatory control over the project being built. (Ultimately, the California Coastal Commission and other state agencies would have to approve the project.)

But Mayor Burton and his peers expressed their desire to voice their concerns early to West Basin’s board of directors while the plant is still in the planning stage. They made it clear that they view the plant as blight on their shorelines, one that would further degrade a marine environment already challenged by nearby industrial impacts. The thought is that enough public pressure might convince the agency to shelve the plan in favor of other water supply options.

Driving home, I thought about the potential appeal of desalination. Strange times, brought on by the scary thought of drought, often bring extreme solutions. Like a shipwrecked crew in a lifeboat terrified of dehydration, some Southern California communities have looked to seawater desalination as an easy way to slake their thirst.

With Southern California importing 80% of its water, it’s understandable why a local water agency would want to become more self-sufficient. West Basin says on its website that the plant could provide “local control of water without the threat of . . . being cut off from the supply.”

Sounds reasonable, right?

Well, speaking as someone not in the lifeboat, I’d suggest to West Basin that there’s water all around them. West Basin is already adjacent to a plentiful source of  water — the City of Los Angeles’ Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant, which currently provides West Basin with 40 million gallons of highly treated recycled water each day.

water — the City of Los Angeles’ Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant, which currently provides West Basin with 40 million gallons of highly treated recycled water each day.

West Basin already has plans to nearly double the water recycling effort to create 70 million gallons of recycled water by 2020. It seems strange that West Basin wants to add a mere 10% to their current water portfolio by jumping into costly and risky desalination—commonly considered a last resort for water-starved communities by everyone from the country of Israel to the chair of Yale University’s Chemical Engineering department. Especially when even more water than what they have projected could be sourced from Hyperion.

Millions of dollars have already gone into scoping this standalone desal plant. That money would have been better spent creating a comprehensive blueprint about how Hyperion and West Basin could better align their interests to dramatically ramp up shared water recycling. (You can read more about the potential of water recycling and stormwater capture here.)

Yes, getting two separate municipal agencies to work together is messy and can be complicated. But too often politics and control-issues trump common sense. West Basin is seeking an autonomous water future, but at what cost?

Because it’s so energy intensive, desalination is not only the most expensive option for drinking water, it also has the potential to put the most carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, aggravating climate change.

Adding to the environmental issues, West Basin’s analyses at this point show that subsurface seawater intake valves appear infeasible at their proposed plant location, forcing the use of exposed, open-ocean intake valves. This means sucking millions of gallons out of the open ocean environment each day, a concept that is completely out-of-step with Heal the Bay’s mission to protect the marine environment.

Not only do open-ocean water intake valves vacuum up fish larvae, the final by-product of desalination is a double-salty toxic brine. That slurry is diffused back out into the ocean, creating a second detrimental impact on marine life. (You can read more about our top 5 concerns with desal here.)

Before jumping into desal, West Basin might learn from other agencies’ mistakes.

San Diego has recently built the Pacific’s largest desalination plant in Carlsbad. Just one month after city officials ceremoniously cut the tape on the plant, city water suppliers in February had to dump more than 500 million gallons of perfectly (and expensively) good drinking water into the Lower Otay Reservoir, near Chula Vista.

Sounds crazy, right?

Under its contract with desal operator Poseidon Resources, the San Diego County Water Authority must buy a certain quota of desalinated water produced by the plant. The only problem is that San Diegans, responding to the Governor’s pleas to conserve during the drought, are doing too good a job of cutting back. San Diego now has more water than it needs. With an overabundance of water supply, San Diego is creating its own scenario from “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.”

Heal the Bay applauds the Manhattan Beach City Council for speaking out about West Basin’s proposed desalination plant and bringing awareness to a situation that has received scant public attention.

We would also like to commend West Basin for their leadership and innovation over their almost 70-year history. They have been a good partner with Heal the Bay and they should be lauded for their efforts on water conservation and current recycling program.

We respectfully encourage West Basin to fully explore expanding their current water recycling programs rather than chase the unicorn of a desal plant.

Heightened water recycling with Hyperion is the most responsible way to increase West Basin’s water supply. It’s also a common-sense initiative that would win very broad support – unlike desal.

Perhaps sometime in the future, we’ll all reconvene for another Tuesday night at the Manhattan Beach City Council watering hole. We can toast the future with a crystal-clear, purified glass of recycled water.

In the meantime, we promise to keep you posted and alert you about opportunities for the public to weigh in on this matter.

Join our mailing list to stay up-to-date on important regional issues like desalination.

![]() Polystyrene is seldom recycled due to its low quality and value, even though it’s designated with recycling code 6.

Polystyrene is seldom recycled due to its low quality and value, even though it’s designated with recycling code 6.

The “Five Kings” is a nickname that has been used for the

The “Five Kings” is a nickname that has been used for the  Early in 2016, Los Angeles County was set to have one of the most stringent used needles and unused prescription medication take-back programs in the country. At the time, only Alameda County (the county east of San Francisco containing Oakland, Berkeley, and Livermore) had such a program in place. This take-back program would ideally take the form of depositories (think mailbox/library book return) in Los Angeles drug stores and other convenient places. Heal the Bay believes that this ordinance will

Early in 2016, Los Angeles County was set to have one of the most stringent used needles and unused prescription medication take-back programs in the country. At the time, only Alameda County (the county east of San Francisco containing Oakland, Berkeley, and Livermore) had such a program in place. This take-back program would ideally take the form of depositories (think mailbox/library book return) in Los Angeles drug stores and other convenient places. Heal the Bay believes that this ordinance will  Months have gone by and the results of the public education program and take-back events have been announced. According to County of Los Angeles Public Health, the pharmaceutical companies’ campaign objectives in summary “

Months have gone by and the results of the public education program and take-back events have been announced. According to County of Los Angeles Public Health, the pharmaceutical companies’ campaign objectives in summary “ Sheila Kuehl stated that the people of L.A. County “should have an easy choice” of where to get rid of their old medications and used syringes. She went on to say that as Supervisors, “it’s our responsibility [to make it happen] and we will take it.”

Sheila Kuehl stated that the people of L.A. County “should have an easy choice” of where to get rid of their old medications and used syringes. She went on to say that as Supervisors, “it’s our responsibility [to make it happen] and we will take it.”