By now, we all know that a swimmer was bitten by a white shark in Manhattan Beach last Saturday. Escape the media feeding frenzy with Heal the Bay scientists Sarah Sikich and Dana Roeber Murray as they inject a dose of reality into the sensationally roiling waters.

Why did this shark bite the swimmer?

A juvenile white shark, approximately 6-8 feet long, was caught by hook-and-line from Manhattan Beach Pier on the morning of Saturday, July 5. After the shark had been struggling for 40 minutes on the angler’s line, a group of ocean swimmers inadvertently crossed its path. As one swimmer passed over the thrashing shark, he was bitten on his side and hand. It is likely that the bite was accidental because the swimmer crossed the shark’s path while it was in distress. Shark experts call this a provoked attack because there was human provocation involved–in this case with a hook, line and fisherman. Any animal that’s fighting for its life is likely to feel provoked and threatened.

Why are there sharks in this particular area?

Santa Monica Bay is home to dozens of shark and ray species. Many of them are small, like the swell shark and horn shark, and live in kelp forests and rocky reefs. Juvenile great white sharks are seasonal residents of Southern California’s coastal waters, likely congregating in Santa Monica Bay due to a mixture of abundant prey and warm water. Manhattan Beach has been an epicenter for sightings over the past few summers. White sharks are frequently spotted by boaters, pier-goers, surfers and paddlers–especially between the surf spot El Porto and the Manhattan Beach Pier. Juvenile white sharks, measuring up to 10 feet, prey mostly on bottom fishes such as halibut, small rays and other small sharks.

What can I do to be safer while swimming in the ocean?

There are risks involved with any outdoor activity, so it’s important to be smart about where you swim. We’d like to remind people that poor water quality, powerful waves, strong currents and stingrays pose a greater threat to local ocean-goers than sharks. Instead of fearing the fin, swimmers should remember to shuffle their feet in the sand to avoid being stung by rays, be aware of lifeguard warnings about currents and waves and check Heal the Bay’s Beach Report Card for water quality grades.

How can I reduce my chances of encountering a shark?

According to the Department of Fish and Wildlife, there have only been 13 fatal white shark attacks in California since the 1920s. Your own toilet poses a greater danger to life and limb than any shark. Swimmers and surfers have frequented Manhattan Beach for generations, and it is commonly known that the area is home to a seasonal population of juvenile white sharks. If you’re still concerned, here are some quick tips to avoid run-ins with fins:

- Avoid waters with known effluents or sewage.

- Avoid areas used by recreational or commercial fishermen.

- Avoid areas that show signs of baitfish or fish feeding activity; diving seabirds are a good indicator of fish activity.

- Lastly, do not provoke or harass a shark if you see one!

What should I do if I see a shark in the water?

First, assess the risk: If it is a small horn shark or thornback ray, it is safe to swim in the area–but keep your distance from the animal. If a larger shark is spotted, like a white shark, it is best to evacuate the water calmly, trying to keep an eye on the animal. Do not provoke or harass the shark. Report your shark sighting, with as much detail possible, to local lifeguards.

If you are one of the few people attacked by a shark (the odds are in your favor at 11.5 million-to-one), experts advise a proactive response. Hitting a shark on the nose, ideally with an inanimate object, usually results in the shark temporarily curtailing its attack. You should try to get out of the water at this time.

Should the city or county be looking at other shark safety precautions?

Los Angeles County lifeguards have a safety protocol of warning ocean-goers to exit the water when there has been a verifiable shark sighting, and this is a good protocol. Lifeguards may also close the beach temporarily to ocean-goers based on the risk. However, closing beaches for long periods of time due to shark sightings or closing piers to fishing will not likely reduce the risk, nor is it consistent with California’s laws or beach culture. We also recommend creating a program to educate sport and pier anglers about how to avoid catching sensitive species like white sharks and how to act responsibly if one is caught.

I enjoy fishing on the pier…what can I do to ensure I’m doing it safely?

If you enjoy fishing, it is best to avoid areas where there are lots of swimmers and surfers in the water. From swimmers getting tangled in fishing line to bait fish attracting predators to the area, fishing where people are in the water is not a good idea. Regarding pier fishing specifically, it’s important to note that many anglers who fish on municipal piers do it for subsistence–to put food on the table. Piers are one of the only places in the state where individuals do not need a fishing license, which reduces expenses and provides public access to fishing for everyone. However, anyone that fishes or hunts anywhere in California must adhere to the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife regulations. These regulations state that “white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) may not be taken or possessed at any time.”

Why are sharks worth worrying about? Why should we protect them?

Sharks are at the top of the food chain in virtually every part of every ocean. They keep populations of other fish healthy and ecosystems in balance. In addition, a number of scientific studies demonstrate that the depletion of sharks can result in the loss of commercially important fish and shellfish species down the food chain, including key fisheries such as tuna.

Despite popular perceptions of sharks as invincible, shark populations around the world are declining due to overfishing, habitat destruction and other human activities. It is estimated that over 100 million sharks are killed worldwide each year. Of the 350 or so species of sharks, 79 are imperiled, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. There are several important spots for Northeastern Pacific white sharks in California, yet they are vulnerable to ongoing threats, such as incidental catch, pollution and other issues along our coast. White shark numbers in the Northeastern Pacific are unknown but are thought to be low, ranging from hundreds to thousands of individuals. They’re protected in many places where they live, including California, Australia and South Africa.

What is Heal the Bay doing to protect wildlife while keeping people safe?

Heal the Bay works toward solutions that benefit both people and ocean wildlife, from advocating for pollution limits and cleaner beaches to supporting marine protected areas and more sustainable fishing practices. We closely monitor new and emerging science to inform these actions.

While fishing for white sharks in California is prohibited, there are no limits on white shark bycatch in U.S. fisheries. Sharks can be entangled as bycatch by set-and-drift gillnet fisheries in their nursery habitats off the coast of California. Although these fisheries target other fish like halibut and white seabass, they also incidentally catch sharks. Heal the Bay has recommended better drift gillnet regulations to reduce shark bycatch, including research to improve fishing practices, and advocating for increased observer coverage for bycatch on fishing vessels.

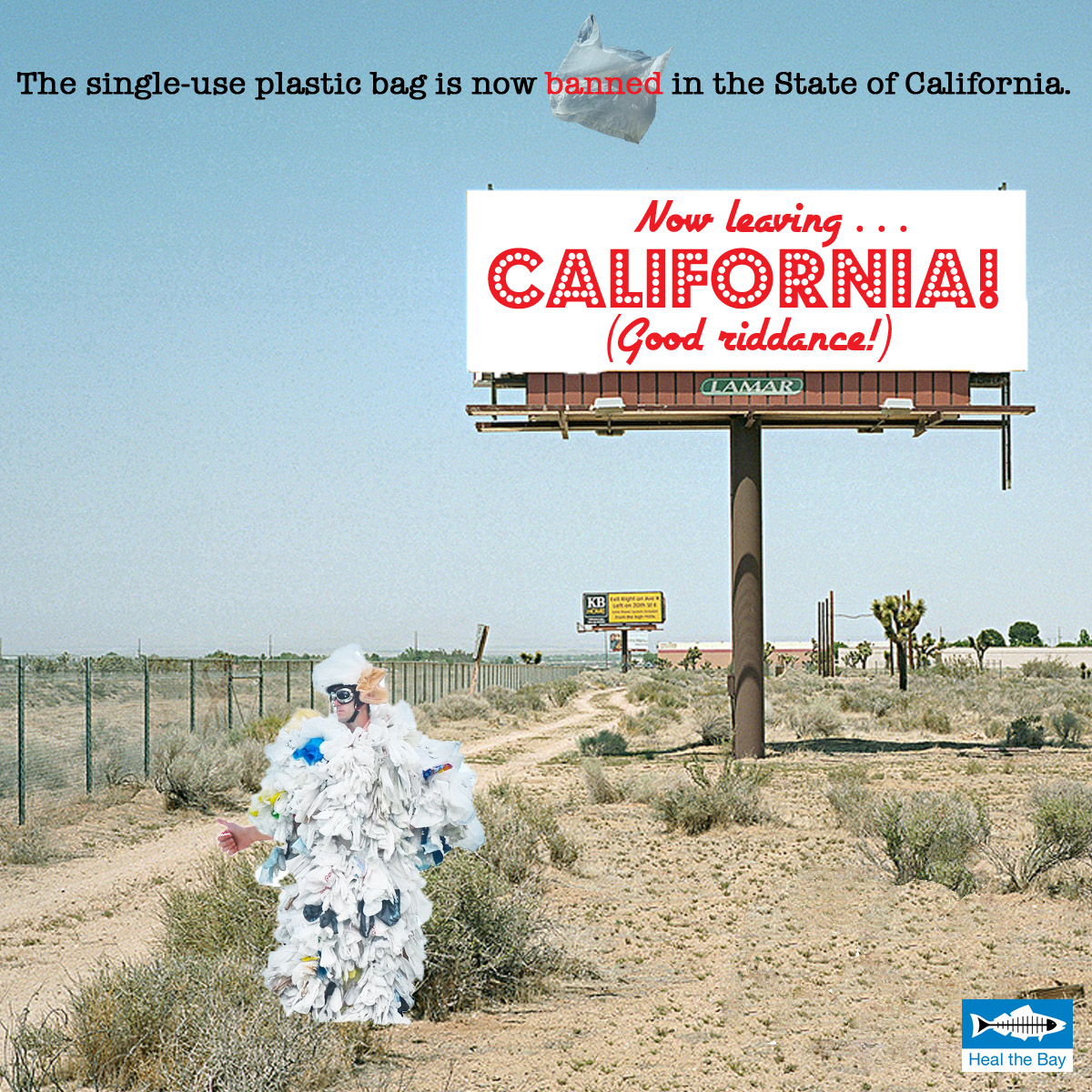

Shark finning, the practice of cutting fins from a living shark and then tossing its body back into the ocean to die, is another threat to sharks. Millions of sharks worldwide are killed for fins each year. Fortunately, states and countries worldwide are banning this practice. In 2011, a Heal the Bay-supported bill passed with tremendous public support, banning the trade of shark fins in California.

Please contact Heal the Bay if you’d like more information on our local shark population, swimmer safety and conservation efforts.

Heal the Bay led the charge to enact a ban in L.A., spurring statewide action

Heal the Bay led the charge to enact a ban in L.A., spurring statewide action

A white shark takes the bait in Shark Alley off the coast of South Africa.

A white shark takes the bait in Shark Alley off the coast of South Africa. A white shark breaching.

A white shark breaching. From inside the shark cage!

From inside the shark cage! Still safely in the cage.

Still safely in the cage.

I cannot imagine what that little shark thought about its first kiss — but I loved it. I won’t do it again. I promise to hold back, because honestly I’m pretty sure that horn shark was pretty upset about the whole incident. So I encourage you to love sharks as much as possible but try to restrain yourself when you feel a “Kiss Attack” coming on. If you are in need of your shark “fix” then I very much encourage you to visit us at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium, where you’ll get an up close encounter with horn sharks, swell sharks and leopard sharks. See you soon and feel free to ask for me by name — the Shark Kisser!

I cannot imagine what that little shark thought about its first kiss — but I loved it. I won’t do it again. I promise to hold back, because honestly I’m pretty sure that horn shark was pretty upset about the whole incident. So I encourage you to love sharks as much as possible but try to restrain yourself when you feel a “Kiss Attack” coming on. If you are in need of your shark “fix” then I very much encourage you to visit us at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium, where you’ll get an up close encounter with horn sharks, swell sharks and leopard sharks. See you soon and feel free to ask for me by name — the Shark Kisser!