Kicking off El Niño Week, Heal the Bay staff scientists and program directors have assembled simple answers to the complex questions about what El Niño may bring to your home, our beaches and greater L.A.

What does El Niño mean anyway?

El Niño is a global climate event that occurs at unpredictable, two-to-seven-year intervals. The hallmark of El Niño is more than a year of above-average surface temperatures in much of the Pacific Ocean. This has impacts on weather over most of the world, but can mean more rain for the southwestern U.S.

The direct translation from the Spanish word means “the little boy.” According to one version of the name’s derivation, Peruvian fisherman noticed a pattern of unusually warmer waters around Christmas time and called it “El Niño” in reference to baby Jesus. Scientists in Peru adopted the name and evolved the meaning when they recognized more intense and irregular changes in climate within seven-year intervals seen throughout the entire Pacific Ocean, not just along the coast of Peru.

What causes an El Niño?

What causes an El Niño?

An El Niño is caused by the prolonged warming water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. It occurs alongside Southern Oscillation, which is the change of atmospheric pressure over the eastern and western Pacific Ocean. Because they happen at the same time, El Niño and Southern Oscillation are often referred to as ENSO. Today, scientists use ENSO and El Niño interchangeably, so El Niño does refer to the entire phenomenon.

With a decrease in atmospheric pressure over the eastern Pacific, we also see an associated decrease in the westward blowing Trade Winds along the equator. This allows the warmer waters to travel north, and during heavy El Niños the subtropical jet stream can move north. The subtropical jet stream usually runs over Mexican and Nicaraguan rainforests. If it were to move over the southwestern U.S. this year, we could see heavier rains and a stronger El Niño.

When is it coming?

We will be feeling the effects of El Niño in the late fall/early winter of 2015. We already have experienced some early signs, with unusual stretches of humidity this summer and our thunder storms in July from Hurricane Dolores (warmer oceanic waters help to fuel hurricanes). The effects are expected to diminish in spring 2016.

Will it definitely bring heavy storms?

Experts predict a 95% chance of moderate El Niño conditions to continue into the winter, which may bring rain to California during a few large rain events. El Niños don’t guarantee rain and can be unpredictable, which is why you probably heard discussion on the matter on-and-off for years without seeing a lot of rain. Some El Niño years have remained dry while others have produced epic rains.

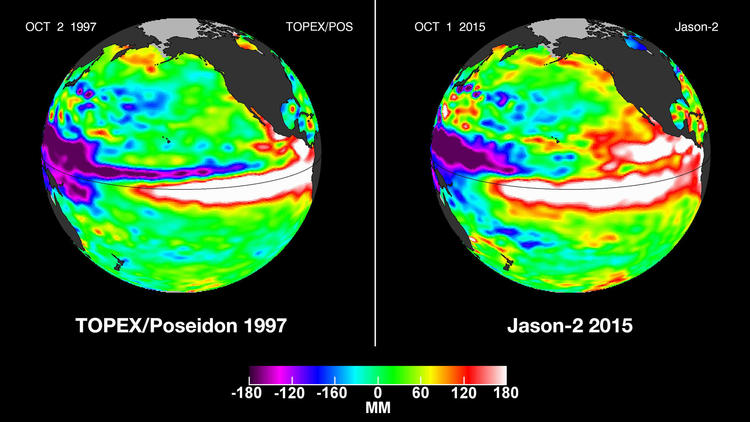

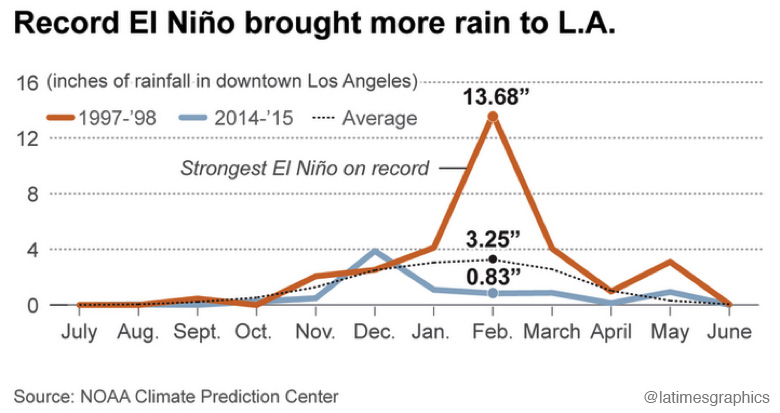

The last major El Niño we saw in Southern California was in 1997-98, and the above average ocean temperatures this summer have mirrored the ones we saw in 1997. As of now, we are seeing predictions of El Monstruo-type storm events this winter.

How much rain are we talking about?

How much rain are we talking about?

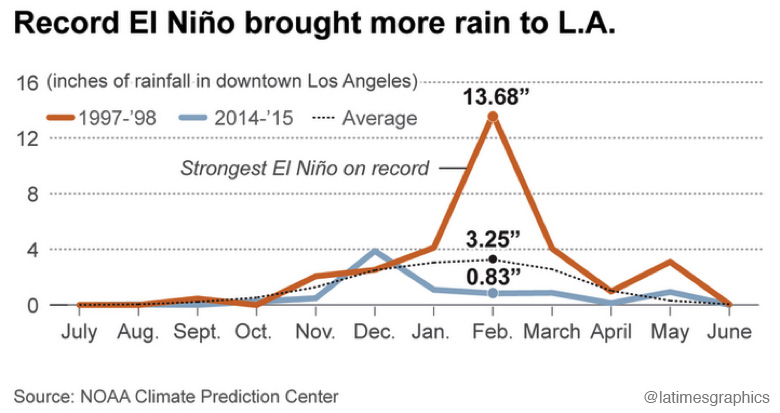

The ocean temperatures suggest that we will see an El Niño that matches, and may even surpass, the strength of the 1997 El Niño, the strongest on record (represented by graph on right). In February 1998, downtown L.A. saw 13.68 inches of rain, which is almost equivalent to a full year’s worth of rainfall seen in only one month. If it does indeed mirror 1997, we could see double the rainfall in Southern California. However, this is all dependent on the wind patterns, which we have yet to see. These uncertainties make El Niño so unpredictable and why we keep speaking in terms of hypotheticals.

What’s a “Godzilla” El Niño?

A Godzilla El Niño refers to an exceptionally strong El Niño that can actually move the subtropical jet stream over California. We have only seen these Godzilla storms in the El Niños of 1982-83 and 1997-98.

What areas in L.A. will likely be hit hardest?

El Niño events can bring much rain to Southern California, which can result in mudslides, erosion and flooding. Homes located in areas known to be at risk of mudslides will likely be hit hardest–for example, houses built on the side of steep mountains or hills. Also, any areas in L.A. that have storm drains that are clogged by trash and debris could experience flooding in their neighborhoods. If you find a gutter that’s blocked, call the City’s Storm Drain Hotline at (800) 974-9794 so that L.A. Sanitation can remove the debris before the rain hits. (And look out for our blog post later this week on how you can better prepare your home for expected rains.)

If it rains, will it mean the drought is over?

No. California has 43 million acre-feet of water storage in reservoirs, and 75% of that storage is located north of Fresno. The majority of the rains are expected to hit Southern California, and currently our regional infrastructure is not set up to store rainwater or dry weather runoff. The system is designed to move rain water to the ocean as fast as possible. Only 12% of Southern California drinking water comes from locally captured rainwater seeping into our groundwater. It might temporarily relieve drought effects, but it is not the silver bullet answer.

A good analogy is relating the drought to using your credit card: an El Niño winter is like paying off the minimum balance on your credit card. You have temporary relief, but you still have a lot of water debt to pay off from the water you took out before. Our depleted reservoirs require much more water to reach healthy and secure levels.”

Is this a sign of the future? Are storms going to continue to be more intense?

Climate change impacts are already happening now in L.A., and can be intensified in an El Niño year. Impacts from climate change along our coasts include increased storm intensity, ocean temperature increases, changing currents, sea level rise, species range shifts, coastal erosion, and ocean acidification. To make matters worse, a combination of impacts may collide during an El Niño year — such as high tides, sea level rise, storm surges, and inland flooding. The projected inundation could severely impact our freshwater supplies, wastewater treatment plants, power plants, and other infrastructure, not to mention public health and the environment. (See our blog post later this week about how climate change could impact local shorelines in Venice and Malibu.)

I thought rain was a good thing. Why is Heal the Bay worried about it?

Yes, we desperately need rain in our drought-parched state. But rain creates urban runoff — the No. 1 source of pollution at our beaches and ocean.

What is “stormwater capture” and why is Heal the Bay so excited about it?

The L.A. region now imports more than 80% of our water from Northern California and the Colorado River watershed, using enormous amounts of energy and capital to do so. In an era of permanent drought, we simply must do a better job of using the water we already have by investing in innovative infrastructure projects that capture and reuse stormwater instead of sending it to senselessly pollute our seas. Runoff — if held, filtered and cleansed naturally in groundwater basins — can provide a safe source of water for human use.

How does rain create pollution?

How does rain create pollution?

Rimmed by foothills and mountains, Los Angeles County is like a giant concrete bowl tilted toward the sea. When it rains, water rushes along paved streets, picking up trash, fertilizer, metals, pet waste and automotive fluids before heading to the ocean via the region’s extensive stormdrain system.

How do stormdrains trash the beach?

With memories of historical deluges on their mind, engineers designed L.A. County’s 2,800-mile stormdrain system in the ‘30s and ‘40s to prioritize flood prevention. Moving stormwater out to sea quickly was their number one goal. But it also has the unintended function of moving trash and bacteria-laden runoff directly into the Santa Monica and San Pedro Bays, completely unchecked and untreated. An average one-inch storm will create about 10 billion gallons of runoff in L.A. County stormdrains. That’s 120 Rose Bowls’ worth of dirty water.

What does all this runoff to do the ocean and the animals that call it home?

Hundreds of thousands of animals each year die from ingesting trash or getting entangled in manmade debris. Seawater laden with chemicals and metals makes it harder for local marine life to thrive and reproduce.

What about the human health impacts?

Beachgoers who come in contact with polluted water after storms face a much higher risk of contracting illnesses such as stomach flu, ear infections, upper respiratory infections and skin rashes. A UCLA epidemiology study found that people are twice as likely to get sick from swimming in front of a flowing stormdrain than from swimming in open water.

How can ocean lovers stay safe during the El Niño months?

- Wait at least 72 hours before entering the water after a storm

- Stay away from storm drains, piers and enclosed beaches with poor circulation

- Go to Heal the Bay’s beachreportcard.org to get the latest water quality grades and updates

How can I support Heal the Bay’s efforts to make L.A. smarter about stormwater?

- Come to a volunteer cleanup to learn more about stormwater pollution and what can be done to prevent it. Invite family and friends to help spread the word.

- Share information on your social networks and support our green infrastructure campaigns.

- Become a member. Your donation will underwrite volunteer cleanups, citizen data-collection efforts and advocacy efforts by our science and policy team to develop more sustainable water policies throughout Southern California.

Heal the Bay staff members Nancy Shrodes, Matthew King and Dana Murray contributed to this report.

The summit wrapped up with time for each club to reflect on what proposed projects would suit their vision for the year and then plot those goals onto a calendar of the school year. As a registered Club Heal the Bay Partner, clubs also learned that participating in three events or netting three reward “drops” would earn them an invitation to our Beachy Celebration which we will host at the end of the school year.

The summit wrapped up with time for each club to reflect on what proposed projects would suit their vision for the year and then plot those goals onto a calendar of the school year. As a registered Club Heal the Bay Partner, clubs also learned that participating in three events or netting three reward “drops” would earn them an invitation to our Beachy Celebration which we will host at the end of the school year.

Oil Spill Response SB 414 (Senator Jackson) helps make oil spill response faster, more effective, and more environmentally friendly by creating a program for fishing vessels to voluntarily join in oil spill response and place a temporary moratorium on the use of dispersants within state waters. Catalyzed by the devastating Plains All American oil spill in Santa Barbara earlier this year,

Oil Spill Response SB 414 (Senator Jackson) helps make oil spill response faster, more effective, and more environmentally friendly by creating a program for fishing vessels to voluntarily join in oil spill response and place a temporary moratorium on the use of dispersants within state waters. Catalyzed by the devastating Plains All American oil spill in Santa Barbara earlier this year,  Mandated Renewable Energy SB 350 (Senator De Leon)

Mandated Renewable Energy SB 350 (Senator De Leon)

How does rain create pollution?

How does rain create pollution?

Then on Tuesday Oct. 13, come back to the Aquarium to learn all the latest on El Niño from Bill Patzert, often called the “Prophet of California climate.” Patzert has been a scientist at the California Institute of Technology’s NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, since 1983.

Then on Tuesday Oct. 13, come back to the Aquarium to learn all the latest on El Niño from Bill Patzert, often called the “Prophet of California climate.” Patzert has been a scientist at the California Institute of Technology’s NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, since 1983.

Staff scientist Dana Murray, center, helped install new signs in Malibu.

Staff scientist Dana Murray, center, helped install new signs in Malibu.

Meeting in her Westwood living room in spring 1985, housewife Dorothy Green and schoolteacher Howard Bennett mobilize a small squad of grassroots activists to conquer ongoing pollution in Santa Monica Bay. Brilliantly taking its mission as its name, Heal the Bay is officially born later that year.

Meeting in her Westwood living room in spring 1985, housewife Dorothy Green and schoolteacher Howard Bennett mobilize a small squad of grassroots activists to conquer ongoing pollution in Santa Monica Bay. Brilliantly taking its mission as its name, Heal the Bay is officially born later that year. Thanks to intense lobbying from Heal the Bay and a federal consent decree, Hyperion Treatment Plant agrees in October 1986 to stop dumping partially treated sewage into Santa Monica Bay. Sewage pollution levels in the Bay have since decreased by more than 90%.

Thanks to intense lobbying from Heal the Bay and a federal consent decree, Hyperion Treatment Plant agrees in October 1986 to stop dumping partially treated sewage into Santa Monica Bay. Sewage pollution levels in the Bay have since decreased by more than 90%. Volunteers Gabrielle Mayeur and Sherry Johannes unwittingly create one of L.A.’s great brands in October 1987. Their evocative and provocative fishbone logo creates instant recognition for the fledgling organization. Whether it’s slapped on a skateboard or a Prius, the fish remains a powerful marker for L.A.’s tribe of ocean lovers.

Volunteers Gabrielle Mayeur and Sherry Johannes unwittingly create one of L.A.’s great brands in October 1987. Their evocative and provocative fishbone logo creates instant recognition for the fledgling organization. Whether it’s slapped on a skateboard or a Prius, the fish remains a powerful marker for L.A.’s tribe of ocean lovers. Aiming to protect the health of millions of ocean users, Heal the Bay publishes its first Beach Report Card in 1992, giving A-to-F grades to local beaches based on levels of bacterial pollution. Developed by outspoken executive director Mark Gold, the grading program shines a bright light and eventually helps secure $200 million in state funds to clean up chronically polluted beaches.

Aiming to protect the health of millions of ocean users, Heal the Bay publishes its first Beach Report Card in 1992, giving A-to-F grades to local beaches based on levels of bacterial pollution. Developed by outspoken executive director Mark Gold, the grading program shines a bright light and eventually helps secure $200 million in state funds to clean up chronically polluted beaches. The first storm drains stenciled for our Gutter Patrol Program in October 1992 reminded would-be litterers that “This Drains to the Ocean.” Volunteers paint more than 60,000 catch basins with our message and logo over two years, connecting residents throughout L.A. County to their watersheds and our work.

The first storm drains stenciled for our Gutter Patrol Program in October 1992 reminded would-be litterers that “This Drains to the Ocean.” Volunteers paint more than 60,000 catch basins with our message and logo over two years, connecting residents throughout L.A. County to their watersheds and our work. Arguing that impaired water bodies in Los Angeles and Ventura counties are not being adequately remediated, Heal the Bay files an intent to sue the EPA in December 1997. A settlement compels the EPA to create 92 “Total Maximum Daily Load” limits over 13 years. With these measurable benchmarks in hand, Heal the Bay can now pressure dischargers to reduce pollution levels or meet stiff fines. The new TMDL model is copied nationwide.

Arguing that impaired water bodies in Los Angeles and Ventura counties are not being adequately remediated, Heal the Bay files an intent to sue the EPA in December 1997. A settlement compels the EPA to create 92 “Total Maximum Daily Load” limits over 13 years. With these measurable benchmarks in hand, Heal the Bay can now pressure dischargers to reduce pollution levels or meet stiff fines. The new TMDL model is copied nationwide. Heal the Bay gets into the aquarium business by acquiring UCLA’s Ocean Discovery Center in March 2003 for the princely sum of $1. The rechristened Santa Monica Pier Aquarium becomes a beachhead for our youth education programs. We’ve since inspired more than 1 million guests to become better stewards of our local ocean and watersheds.

Heal the Bay gets into the aquarium business by acquiring UCLA’s Ocean Discovery Center in March 2003 for the princely sum of $1. The rechristened Santa Monica Pier Aquarium becomes a beachhead for our youth education programs. We’ve since inspired more than 1 million guests to become better stewards of our local ocean and watersheds. After years of pressure from Heal the Bay, Washington Mutual agrees in November 2003 to sell Ahmanson Ranch at the headwaters of the Malibu Creek watershed to the State of California. The coalition of environmental advocates, scientists and celebrities successfully preserves 2,300 acres of open parkland and 20 miles of streams, thereby reducing pollution and protecting several threatened species.

After years of pressure from Heal the Bay, Washington Mutual agrees in November 2003 to sell Ahmanson Ranch at the headwaters of the Malibu Creek watershed to the State of California. The coalition of environmental advocates, scientists and celebrities successfully preserves 2,300 acres of open parkland and 20 miles of streams, thereby reducing pollution and protecting several threatened species. Ensuring a vibrant local ocean for generations to come, Heal the Bay’s policy staff leads an often contentious process with the state and anglers to create 52 Marine Protected Areas along the Southern California coast in January 2012. Our most biologically rich underwater habitats get a reprieve from human pressures, allowing depleted stocks in such areas as Malibu and Palos Verdes to recover and thrive.

Ensuring a vibrant local ocean for generations to come, Heal the Bay’s policy staff leads an often contentious process with the state and anglers to create 52 Marine Protected Areas along the Southern California coast in January 2012. Our most biologically rich underwater habitats get a reprieve from human pressures, allowing depleted stocks in such areas as Malibu and Palos Verdes to recover and thrive. Heal the Bay’s programs and policy staff spearhead a plastic bag ban in Los Angeles, which in January 2014 becomes the largest city in the nation to take on Big Plastic. The unanimous City Council vote triggers a nationwide debate about sustainability and catalyzes other bans throughout the country.

Heal the Bay’s programs and policy staff spearhead a plastic bag ban in Los Angeles, which in January 2014 becomes the largest city in the nation to take on Big Plastic. The unanimous City Council vote triggers a nationwide debate about sustainability and catalyzes other bans throughout the country.