June 14, 2016 — Students at Cal State L.A. have been sharing their observations with us about the plague of plastic pollution. Here’s a report from the Eastside, penned by students of Lollie Ragana, an English professor on campus. In the coming days, we will publish a few of our favorites.

BRIGIDO AYON

Plastic is part of our daily lives. But the use of plastic has come to haunt us, as it is part of the huge amount of trash we throw away. In the Los Angeles area alone, “10 metric tons of plastic fragments—like grocery bags, straws and soda bottles—are carried into the Pacific Ocean every day,” according to Ecowatch.

I commute to school at Cal State L.A. and in order to get to my destination I must take the freeway as it is much faster, at times, and more direct. Most of the time I have to deal with bumper-to-bumper traffic. As I am slowly making my way to school, I wonder about and recognize a lot of trash lying on the side of the freeway and on the on/off ramps.

As I pay closer attention to the highway, I realize that most of the trash is plastic or contains parts of plastic. “On average in Southern California alone Caltrans picks up about 50,000 cubic yards of trash on our freeways,” according to a recent ABC News report, with three quarters of that trash being plastic in nature. We as consumers need to be educated about the use of plastic and the realization that plastic does not go away. Nearly 50% of the plastic we use, we use just once and throw away, according to Ecowatch. This shows that we pay little attention to the amount of plastic we use and throw away after one single use.

One of the off-ramps that I mainly use is covered with plastic trash and also has a fence that has a lot of the trash pinned up against it. At times I put my windows down to get some fresh air, but instead I receive a hideous smell that I believe comes from all the trash on the off-ramp. The worst part is after a rainfall, like the few we’ve experienced recently, which makes the trash smell worse and gives off a moist, garbage-disposal stink.

As a daily commuter, I feel that most people in my community aren’t aware of the amount of plastic trash that ends up in this one spot alone. I have asked other friends who use the off-ramp if they have noticed the trash when exiting and most of them respond with a surprised gesture. They feel that it’s too difficult to pay attention to the trash when driving. But I feel as if they are afraid to admit that there is a huge plastic trash problem surrounding that area.

I feel that certain steps need to be done in order to change the off-ramp from a plastic dump to a clean area. One of the steps is to put up posters and signs in order to make the people aware of the amount of plastic being thrown near the off-ramp. Once the signs are posted, volunteers can help clean up the trash and dispose of it properly. Also, we can have community seminars where we present the dangers of using plastic and the proper way to dispose of it. This will help open up the eyes of many which will then lead to the contribution of cleaning many other areas common to the off-ramp.

The highways and the off-ramp need to be cleaned by the community because of how bad it looks and the awful smell it gives off. In the end, I want to be able to drive through the off-ramp and be satisfied with its appearance and not have to have my windows rolled up when I pass through the area.

MARIA ARAUJO

Our problem is that we don’t know the problem. Most of you have been to a beach, or at the least, passed by one. Isn’t it just nearly the perfect view? The perfect evening can also instantly turn into an uncomfortable situation, as you may not be able to properly walk on the polluted sand. Most of the things found on beaches are single use products such as water bottles, straws, fast food wrappings, and even personal belongings. The majority of the things that are found on the beach are made up of plastic. According to Katie Allen, an education director from Algalita Marine Research and Education, “recently, a team of researchers from six countries calculated that an astounding 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 269,000 tons can be found floating in the global ocean”. As part of the environment, we should be aware of how much we are actually affecting not only the oceans, but also the marine animals, with our waste. I don’t believe that many of us have a clear understanding of how plastic actually works.

Our problem is that we don’t know the problem. Most of you have been to a beach, or at the least, passed by one. Isn’t it just nearly the perfect view? The perfect evening can also instantly turn into an uncomfortable situation, as you may not be able to properly walk on the polluted sand. Most of the things found on beaches are single use products such as water bottles, straws, fast food wrappings, and even personal belongings. The majority of the things that are found on the beach are made up of plastic. According to Katie Allen, an education director from Algalita Marine Research and Education, “recently, a team of researchers from six countries calculated that an astounding 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 269,000 tons can be found floating in the global ocean”. As part of the environment, we should be aware of how much we are actually affecting not only the oceans, but also the marine animals, with our waste. I don’t believe that many of us have a clear understanding of how plastic actually works.

So first — what is plastic? Is there really ever an “away” for plastic?

Many of us may assume it disappears the instant that we throw it away, but the answer is no, plastic never goes away. As far as our understanding for the disposal of our waste goes, we have grown to the idea that by throwing something away we are getting rid of it forever. Now, if you think about it, most of the trash found in the oceans comes from storm drains, which is the same trash we dispose of. When it rains all the trash that goes into the storm drains eventually end up not only in piles of polluted trash, but also floating in the ocean. The real question is, how much can plastic waste damage our environment?

All the plastic waste that ends up floating above or beneath our waters break down into smaller pieces as time goes by. For example, a simple water bottle can end up decomposing into hundreds of little pieces and that doesn’t mean it has finally gone away. It has simply changed its form.

Several marine animals tend to swim with an open mouth in order to consume their food or what they think may be a food source. Since there are millions of tiny plastic pieces floating around, many of them tend to mistake this plastic as food or even as other marine animals. Once the smaller fish eat those plastic pieces, and are eaten by bigger fish and so forth, those plastic pieces become part of the food chain. If the fish are not eaten by their predators, they die due to the inability to digest plastic.

Recently, I’ve learned about something known as The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. As stated by an online source, “The gyre has actually given birth to two large masses of ever-accumulating trash, known as the Western and Eastern Pacific Garbage Patches, sometimes collectively called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” It is said to be about twice as big as the size of Texas.

Can you imagine the millions of tons of waste that will never go away? As mentioned in a Los Angeles Times article, “Nearly 90% of floating marine litter is plastic.” That is an immense amount of plastic waste that continues to increase as greatly as our consumption.

To prevent and even reduce the high percentage of waste in our oceans, we can cut back the use of plastic. We can do things like avoid the use of single use plastic bags, switch our water bottles for reusable steel bottles, or consider changing your home appliances for the ones that are considered to be environment safe. Even spreading awareness of the situation can help create a positive impact for our environment.

It is essential for us to know what we are being exposed to and how safe we maintain the environment because what may affect us today can affect our generations yet to come. Overall, we can get a pretty clear idea of how dangerous pollution, specifically plastic pollution can be by knowing how much plastic pollution is actually affecting our environment. Remember, we are a part of the marine food chain. The birds and fish we see lying dead with plastic pieces in their stomach, could be us lying with toxic chemicals, sooner than you think.

JONATHEN HERNANDEZ

“I can’t wait to go and explore the world!” I used to always tell myself that as I looked out the window and just saw more and more concrete buildings and cars whooshing by. With the window open I could feel the wind hit my face and I just wondered how the wind felt in Europe, or in the Arctic, or even in the middle of the ocean. Alas, those were only child dreams. Even if I kept those dreams alive, they would eventually hurt me; the world isn’t the same as it used to be back in 2000.

Isn’t it fascinating how we say: “Back in 2000” like it’s already been over 50 years? That’s how far the world has come in 16 years, back when everything was relatively cleaner than it used to be. There is only one thing you can blame for the toxins that riddle our drinking water, our food, our oceans, our planet — greed. Looking back at my childhood after cleaning up Dockweiler Beach, it made me look at the world in a different way.

As a little kid I used to love to go to the beach and play in the water, but I had a traumatic experience one time that kept me out of the water. In a way, after learning all that I know about the toxins in the ocean and pollution, I’m thankful I was scarred from almost drowning at the beach at the age of 8. I can only imagine what could be in my system that I picked up from 8 years in the beach water, but I know it’s significantly less than if I had been in the ocean water for 18 years.

I have someone in my life whom I hold dear to my life, and she likes to play in the water at the beach, but, unfortunately, my fiancee can no longer play in the water because I fear for her safety. I thought government regulated places such as beaches would be safe from this hazard, but I was wrong. I now realize it takes more than the government, it takes voices, not just from one person, but from the 7 billion people in this world. We cannot live any longer in this toxic planet. We’re killing ourselves and we need to come together and spread our concern to everyone because if we don’t, we have two paths: The path to death, or the path to redemption.

JESUS HARO

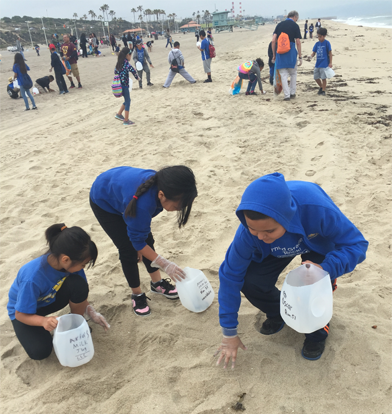

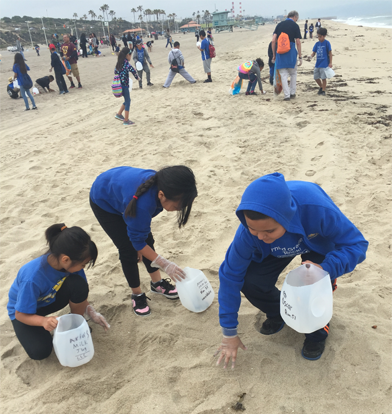

I volunteered on April 17, 2016 in my first beach clean-up at Dockwielder Beach for about two hours. From 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. I picked up plastic and any harmful products in the beach that can hurt the animals in the sea. The beach clean-up included my classmates from my English class.

I wasn’t expecting to see as much plastic and trash as I did that day. I was amazed by how much plastic and trash there was lying on the sand from people enjoying their day at the beach and leaving personal things behind. Also, the numerous over-flooded trash cans caught my attention quickly.

The plastic items lying around the over-flooded trash cans showed the trash cans are not changed frequently. All trash cans should be changed more frequently to prevent the trash cans from overflowing. Changing the trash cans can be a huge help in decreasing the amount of plastic and trash left on all the beaches, not just Dockwielder Beach. It’s obvious people do not throw away their trash because of the over-flooded trash cans, nor they do they want to take their trash with them.

Volunteering in the beach clean-up was my first eye opener about the environment. It made me realize how the people ahurt the environment — not just the environment of us humans, but for the animals in the sea as well. Eventually, the plastic and trash in the sand will find its way to the ocean water. Sea animals are not clever enough to know it’s plastic, so they tend to swallow plastic. Plastic is a major cause of sea animals’ death around the world. It has been a problem since plastic was created.

As for myself, I didn’t know much about how plastic is hurting us and the sea animals around the world. My environmental eye opener began in my college English class about a month ago. Many of my classmates have said they weren’t aware of how bad plastic was for the environment. Having discussions about plastic during class sessions has made me aware of the plastic around me.

The beach clean-up changed my views on the environment because it made me realize how small pieces of plastics and trash can make a beach look bad. Throwing those small pieces of trash and plastics into a trash can make a massive difference.

Being able to experience and be a part of a beach clean-up, plus knowing the amount of plastic and trash we picked up as a team, made me feel great! Even though we did not make a dramatic change by cleaning up for two hours, it was a great feeling knowing I was a part of a team.

I encourage others to volunteer in beach clean-ups and other programs improving the environment. It’s a good way to help the environment we live and breathe in, also the sea animals’ environment. Having people volunteering in beach clean-ups is a great way to make the beaches look nice and clean again and save sea animals.

VALERIA TEMBLADOR

My favorite place to go that allows me to forget about all my problems is Seal Beach. I love walking down the pier passing by all the local shops. With each step that I take, a variety of food aromas sweep me off my feet. I continue to get closer and closer to the beach. Just smelling the sea salt, hearing the waves crash, and the sand running through my toes makes it the most beautiful and soothing place to go. However, this soothing place is not so beautiful when you examine it closer. Seal Beach is one of the many contributors to the pollution that is found in our waters.

Every time I walk on the pier, I see small pieces of trash that get swept away by the wind. However, I was never bothered by it because I never saw the harm, especially from small pieces of trash, until the beach clean up assignment. The cleanup made me realizes we have a major issue on our hands. In our oceans, “ there are 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris,” according to the National Geographic. All the trash we do not pick up gets pushed closer and closer to our waters.

If we continue to neglect the trash from piers or even boardwalks it will eventually come back to us. All we care for is the fun the pier provides, the food, the music, and just having fun in the sand. As of right now many of us do not take action because it has not affected us drastically. Why are we waiting for the damage to get worse? Animals are not the only ones affected by the trash; so are we. The oxygen, which we breathe, will not be as fresh and the water we drink will not be drinkable. So, why are we waiting? We need to start making changes in our communities that are near water. We need to start taking action now before it’s too late.

In order to minimize waste on the Seal Beach Pier, numerous trash cans should be placed all around the pier. However, just simply adding trashcans and placing them all around the pier is not enough. These trashcans get overfilled and they should be replaced hourly to avoid trash falling, which will eventually get blown to the beach. Another way of keeping our beaches clean is having oceanographers hold seminars in order to educate us on how our trash is affecting our water. Lastly, having people volunteer to do beach clean ups weekly will maintain our beaches.

The way we dispose of our trash so freely needs to be recognized before it’s to late. In the end, I want to be able to walk on the pier without fearing that the trash I dispose of will end up in the water. I want my happy place to be beautiful and soothing, not just for me, but also for everyone that enjoys the connection that the pier has with the people.

YVETTE CASTILLO

What’s that smell? As I glanced down the street pavement I quickly got my answer.

A powerful, protruding odor was coming out of a small cigarette butt that was left lying on the street pavement. As I slowly picked up the cigarette and made my way to the nearest trash bin, I began to see more and more cigarette butts on the concrete pavement

LA natives are constantly on the go and it is highly common for one to be on the go and see thousands of cigarette butts left behind by cigarette users. On a bad day one can see a whole pavement covered with cigarette butts.

An average smoker consumes about two packs of cigarettes a day according to no-smoke.org, making it extremely easy for one to misplace and leave the cigarette butts unattended. Leaving the unattended cigarette butts can lead to many negative and unpleasant ailments from pedestrians to inhale the second hand smoke to many animals in taking and eating the cigarette butts.

After seeing documentaries and hearing a speaker from Heal the Bay talk about the dangers of unattended waste, I am aware of the negative consequences that it has not only on human but also to wildlife. However, it was not until I saw a bird trying to eat leftover cigarette butts that it hit a nerve within me.

It is bad enough that unattended cigarettes butts release toxic chemicals into our air, but to see a bird mistake unattended cigarette butts for food was extremely shocking to me. Knowing that the cigarettes are harmful and seeing personally the effect it has on the birds has made me become an advocate for picking up waste such as cigarette butts.

Although one does not have to be a pedestrian to care about this issue, one has a reason to be concerned due to the fact that the toxic pollutants negatively affects wildlife and our lives as well By living in a very populated city such as Los Angeles, we have a high probability of leaving unattended waste such as cigarettes.

Los Angeles County now has the opportunity to address the problem, such as by increasing the number of cigarette bins so anyone can discard their cigarettes without leaving them on the street . By adding more cigarette bins on streets we can make a huge impact on reducing the amount of cigarettes found on local streets.

Although many will disagree with adding more cigarette bins due to the increase in taxes, the ends will justify the means. By paying a little more in taxes for the cigarette bins, we will reduce the number of deaths within wildlife and lower human medical bills. Therefore, it is highly important that one writes to their nearest representative in order to address this problem

Let’s start saving our lives and wildlife by disposing properly of our cigarette butts.

ANA MENDOZA

(Ana wrote a note to a local bag manufacturing plant. It’s printed here.)

Superior Plastic and Paper Bags

1930 E 65th St.

Los Angeles, CA 90001

Dear Mr. Penhashian,

Hello, Mr. Penhashian, my name is Ana Mendoza. I am currently a student at California State University of Los Angeles. The reason I am writing to you is because, in my English class, we are learning about the environment. One of the things that caught my attention is how plastic bags are being thrown out into the streets after being used and are then being washed into the oceans. In order to help the environment, I ask for your help to stop producing any type of plastic and instead produce reusable bags.

After experiencing a beach clean-up, I was able to see how plastic bags are harming our beaches and streets. You might not know what animals in the ocean are going through, but if you were to go to the beach you would become aware of what harm plastic bags are causing.

One of the things I would suggest you to do is to think about, instead of creating plastic bags, making recyclable bags so that people can continue to use them after buying their groceries instead of just throwing them into trash cans and the wind blowing them away into the streets.

According to an article called“The Great Plastic Tide”: “While doing simple walk in the coast line of the beach you can see how there are tiny plastics in the sand.” After reading this statement it made me think about all the animals in the oceans that are being killed because they are eating plastic. Another article in The New York Times talks about how fish in the North Pacific ingest up to 12,000 to 24,000 ton of plastic. After reading this article what caught my attention the most was how fish in the ocean are being killed due to all the plastic there is. I also began to think about how one small change can save hundreds of fish in the sea.

The reason I am against plastic bags is because any hunting mammal that is in the ocean can mistake the plastic bags for a meal and find its airway cut off. The more plastic bags are created the more deaths of mammals are being caused and the deaths by plastic bags are increasing every year.

If you were to start producing reusable bags and explain to your workers why you will not be producing plastic bags anymore I am sure that your workers will also become concerned and they will start to understand that plastic bags are causing harm. If you were to start producing reusable bags, your company will help save the environment. Your company will produce more bags because more store owners are becoming aware of the harm plastic bags are causing and are looking for companies that are beginning to produce reusable bags.

After being able to show you the harm that plastic bags and other objects are causing to fish, I ask for you to stop producing plastic because it might not be harming you right now but in a few years more and more animals will be dying.

Thank you for your time and I hope to hear from you soon in regards to creating reusable bags.

Sincerely,

Ana Mendoza

Thanks to English professor Lollie Ragana for sharing these insights with us.

Our problem is that we don’t know the problem. Most of you have been to a beach, or at the least, passed by one. Isn’t it just nearly the perfect view? The perfect evening can also instantly turn into an uncomfortable situation, as you may not be able to properly walk on the polluted sand. Most of the things found on beaches are single use products such as water bottles, straws, fast food wrappings, and even personal belongings. The majority of the things that are found on the beach are made up of plastic. According to Katie Allen, an education director from Algalita Marine Research and Education, “recently, a team of researchers from six countries calculated that an astounding 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 269,000 tons can be found floating in the global ocean”. As part of the environment, we should be aware of how much we are actually affecting not only the oceans, but also the marine animals, with our waste. I don’t believe that many of us have a clear understanding of how plastic actually works.

Our problem is that we don’t know the problem. Most of you have been to a beach, or at the least, passed by one. Isn’t it just nearly the perfect view? The perfect evening can also instantly turn into an uncomfortable situation, as you may not be able to properly walk on the polluted sand. Most of the things found on beaches are single use products such as water bottles, straws, fast food wrappings, and even personal belongings. The majority of the things that are found on the beach are made up of plastic. According to Katie Allen, an education director from Algalita Marine Research and Education, “recently, a team of researchers from six countries calculated that an astounding 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 269,000 tons can be found floating in the global ocean”. As part of the environment, we should be aware of how much we are actually affecting not only the oceans, but also the marine animals, with our waste. I don’t believe that many of us have a clear understanding of how plastic actually works.

Biological communities in streams are assessed through the different types and numbers of aquatic bugs (or benthic macroinvertebrates) that live there. Think of snails, worms, crayfish, and larval stages of dragonflies, damselflies, black flies, and mayflies. Which brings us back to why we or anyone should care about bugs.

Biological communities in streams are assessed through the different types and numbers of aquatic bugs (or benthic macroinvertebrates) that live there. Think of snails, worms, crayfish, and larval stages of dragonflies, damselflies, black flies, and mayflies. Which brings us back to why we or anyone should care about bugs.