Sept. 21, 2015 — Each day, the Hyperion Treatment Plant discharges hundreds of millions of gallons of treated wastewater into Santa Monica Bay. Thanks to the work of Heal the Bay 30 years ago, this effluent is now cleansed and sanitized to a “secondary treatment” level that greatly minimizes the amount of pollutants that can make people and animals sick.

The treated wastewater eventually makes its way to the ocean via a pipe that runs five miles under the sea at the southern end of Dockweiler Beach.

Unfortunately, this pipe and a massive pump require maintenance repairs after running continuously for the past 54 years. LA Sanitation will be making needed fixes Sept. 21 through Nov. 2.

The city of Los Angeles will discharge the wastewater through a one-mile emergency pipe and outfall during this time period.

Heal the Bay is concerned that a temporary outfall location located just a mile offshore – in much shallower, warmer waters — could have potential impacts to human health, animal life and create an increased risk of harmful algal blooms (HABS). As such, we are working closely with city officials to ensure that impacts are minimized, extensive monitoring occurs, and the relevant information is conveyed to the public in a timely manner. We will be closely evaluating bacteria samples collected by the city of Los Angeles to determine if levels are exceeding health standards and impacting ocean users.

For the next five weeks, we will be providing regular updates about project progress and water quality at impacted beaches. You can also access real-time information via our Beach Report Card Twitter feed.

Note: The County of Los Angeles issued an official closure of Dockweiler State Beach on 9/23 because of bacteria exceedances and the presence of sanitary waste items and hypodermic needles along the shoreline. Those beaches were officially re-opened on 9/26. A phytoplankton bloom stretching for miles was confirmed on 9/28.

Latest Updates

Noon, Monday, Nov. 2: Use of One-Mile Outfall Discontinued

As of midnight last night, the diversion to the one-mile outfall has ceased. Hip hip hooray! Treated effluent is now being discharged from the five-mile outfall, which reduces the chances of blooms and other near-shore impacts.

The latest chlorophyll measurements have been low, indicating that phytoplankton blooms are not currently present in the Bay. Last week’s high winds and strong offshore currents greatly dissipated the effluent plume and all bacterial samples taken on Oct. 31 passed bacterial compliance levels. For a list of which beaches were tested, visit the project site at: http://www.sccoos.org/projects/hyperion/2015/

We want to thank everyone who has helped us stay current on the latest in trash and phytoplankton movements during this process. We couldn’t do what we do without such helpful supporters! And as always, don’t forget to check the Beach Report Card every week for the latest grades at your favorite beaches.

5 p.m., Friday Oct. 23: Red Tide Testing Under Way

The newest grades for our local beaches impacted by the Hyperion discharge are posted and can be found at http://brc.healthebay.org/

Now as for the algae. Green, brown, and red patches of color and blooms have been seen in areas of Santa Monica Bay over the last week. While much of the country gets fall colors in the tree canopy, we seem to have gotten them along our shoreline this year. None of the samples taken so far have found any harmful algae or phytoplankton species. However, there will be sampling tomorrow both offshore and in the two King Harbor Basins. We will let you know when they have assessed those samples to determine their content.

What does that mean for this warm weekend as you get ready to go to the beach?

- Check your grade! Bacteria levels and the color of the waves aren’t always related. So make sure that your beach has received a good bill of health (despite its recent color).

- If anything seems really unusual or foul, report it. Let the lifeguards know, and send us a photo with your exact location and the time you were there. That helps us to track any large changes over time.

- Have a good time! So long as your beach has gotten a good grade, and you’re swimming away from piers, storm drains, and enclosed beaches, you have nothing to worry about,. So go out there and catch some waves!

5 p.m., Wednesday Oct. 21: Red Tide Spotted in Redondo

This weekend foamy brown and green waves washed ashore along South Bay beaches. It’s a sight not seen often along our normally clear coastline, and a source of concern for local beachgoers given all the emails and photos we received. While the thickly colored and foamy waves seem like an exaggerated Hollywood depiction of polluted water, the cause of these waves is actually a fascinating scientific phenomenon.

During the Hyperion Treatment Plant diversion, a plethora of nutrients that are normally piped out five miles of shore has been flowing out just a mile off our coastline while repairs are done to the pumps in the five-mile line. This nutrient flow is a byproduct of the sanitation process, containing nitrogen and phosphorus that have made their way to the wastewater treatment plant from human waste, food, soaps, and detergents. The sanitation process removes harmful bacteria and some of the nutrients from our collective waste, but some of the nutrients remain in the effluent. These nutrients comprise a pre-Thanksgiving feast for the algae and diatoms (together known as phytoplankton) found in our waters. This massive food source, combined with warm water, sunny skies, and strong ocean current, has turbocharged the growth of the colorful blooms seen recently near Hyperion.

But what about the froth and foam along the shoreline? For that, we have diatoms to thank. Diatoms are glass-shelled phytoplankton that not only contain chlorophyll, but also the yellow-brown photosynthetic pigment known as xanthophylls.

Xanthophylls are what give the water the distinct brownish color. When the diatoms are agitated by waves or by winds, they break up, thereby releasing the oils they use to store their food reserves that in turn cause foam. The discoloration is not harmful to the public nor the marine animals. Nor is it harmful to the environment unless the diatoms increase to such tremendous numbers that oxygen in the ocean becomes locally depleted.

Unfortunately, we are currently seeing a growing red tide throughout the South Bay, concentrated near the King Harbor area of Redondo Beach. USC scientists working with LA Sanitation are currently sampling the water in order to determine the content and concentration of this phenomenon.

We are concerned about these circumstances, as massive algal blooms that persist for long periods of time can deoxygenate the aquatic environment and result in the die-off of animals that live along the seafloor. So far, the changing currents have kept the blooms from persisting in one location for extensive periods of time, reducing the risk of harm to our ocean habitat.

However, we continue to track the frequency and intensity of the blooms. Tips from beachgoers help us track the situation. Please send us any photos of massively discolored or foamy waves and let us know their exact location. You can email them to lgriffin[AT]healthebay.org, or post them to our Facebook page. While we hope that this red tide doesn’t persist, we need beachgoers to help us document the situation if it does.

On the fecal indicator bacteria front, the most recent data show no exceedances at the South Bay beaches that were sampled on Oct. 19. For a list of sampled beaches and if they have passed or exceeded limits, visit this project website. You can scroll down to the table “Shoreline Fecal Indicator Bacteria” for latest results.

3 p.m., Thursday, Oct. 15: More Blooms As Far North As Venice

Observations of patches of discolored water continue, with the most recent patch extending North from Venice. The color of the water has been reported as an olive-green consistency throughout the first two meters of the water column. This area is experiencing high concentrations of chlorophyll (a representation of phytoplankton concentration). Each of the phytoplankton bloom patches that we have seen in the bay over the last several weeks have dissipated quickly, and we hope that the story is the same here. We will be keeping an eye on the situation with help from scientists at LA Environmental Monitoring Division, UCSB, and USC. On the 13th (the most recent sample data available) all water quality samples taken by LA Environmental Monitoring Division passed water quality standards.

4 p.m., Tuesday, Oct. 9: L.A. City Council Demands Answers

On the heels of the Oct. 8 hearing at the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board, L.A. City Councilmember Mike Bonin introduced a motion today to ensure that City Council is fully briefed on the cause of the MOSO discharge from Hyperion last month. Bonin, whose district includes affected beaches, asked for concrete actions to keep a similar incident from happening again. Amid growing public concern, the motion requires that Hyperion officials report to the Board on the status of their investigation within three weeks, and that the city assemble a Bay Emergency Response Team that includes various stakeholders, including NGOs such as Heal the Bay, to assist with public notification during spills and other emergency events. The motion also calls for better public education on what should and should not be flushed down toilets. Tampon applicators, condoms and syringes have no business being sent to Hyperion in the first place!

At a media event organized by Councilmember Bonin, Heal the Bay president Alix Hobbs discussed our work to update the public about discharges from Hyperion and hold officials accountable. We hope to use this incident to improve our city through better education as well as better use of our precious water resources. In a time of extreme drought, we should be recycling treated wastewater instead of sending it uselessly to sea. And we should be capturing stormwater instead of seeing high volumes of runoff inundate an already-taxed Hyperion during rainy weather.

You can read more about the council’s action here.

7 p.m., Thursday, Oct. 8: Regional Water Board Demands Accountability

What happened at Hyperion after the epic rainstorm on September 15?

That was the question of the hour—well, four hours, actually—at today’s Regional Water Quality Control Board meeting in downtown L.A., where representatives from the Regional Board, LA Sanitation, Hyperion Treatment Plant, and Heal the Bay contributed testimony on the Hyperion MOSO discharge. What systems failed that led to hundreds of pounds of plastic waste washing up at beaches from Ballona Creek to Manhattan Beach—waste that included hazardous materials like tampon applicators, used condoms and syringes?

The verdict: No one really knows.

“Despite our best laid plans, things have not gone as expected,” said an L.A. Sanitation spokesperson, during the public comment section of the meeting. She added that “there is not an obvious answer” to the question of why this MOSO was discharged from the temporary 1-mile outfall after a 2” rainstorm pummeled the Southland.

The lack of an explanation for the discharge set the stage for comments from Heal the Bay’s James Alamillo, who pointed to the 1,500 online signatures obtained from concerned citizens in less than 24 hours as proof positive of the urgency of the situation. “In 20 years of cleanups, there has never been a cleanup event with this kind of [MOSO] material. At stake is not only our tourism-based economy, but a potential violation of a stormwater or NPDES [National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System] permit. We need to make sure that an event like this doesn’t occur in the future, and we need to find the true cause.”

So what needs to happen—and how long will it take—to determine the cause of the discharge?

Regional Board member Madelyn Glickfeld had a bold suggestion: “We need the best sewer plant operator in the world to come review our system.” Board Executive Officer Sam Unger also reported that engineering resources from the EPA will be brought in to examine the inner workings of Hyperion to determine if any improvements in protocol can be made. In terms of the timeline of the investigation, a full report will be presented at the Regional Board Meeting in January.

After an hour of complex and jargon-heavy back-and-forth between the Board and L.A. Sanitation and Hyperion officials, something different captivated the room: The passionate, emotional testimonies from two L.A. beach-goers who decided to attend the meeting after seeing our Action Alert online. “I am deeply concerned that there is only a net between me and a sewage pipe,” said Sarah Spinuzzi, a surfer and recent law school graduate specializing in water issues. Echoing her sentiment was Rebecca Fix, a lifelong Angeleno who advocated for “exceptionally clean water, not just acceptably clean water.” Board Vice-Chair Irma Muñoz commended Sarah and Rebecca for speaking out, and urged city and county agencies to better utilize the communications networks of grassroots organizations like Heal the Bay to improve the dissemination of information pertinent to public health.

Alix Hobbs, Heal the Bay’s president, sees the MOSO discharge incident as an unfortunate reminder of days we thought were long-past: “We’re having conversations that hearken back to the ‘90s about sewage spills when we should really be collaborating around water recycling.” She’s optimistic about the incident catalyzing a shift toward smarter water management, which will require all stakeholders involved to work together for a more resilient—and less trashy—water future.

As El Niño threatens to deluge Southern California this winter, the question looms: Can Hyperion withstand the impending onslaught? Water Board officials recommended taking some of the burden off Hyperion by diverting heavy stormwater flow to other treatment plants. With rain predicted in the coming week, and three weeks remaining in the 5-mile outfall repair project, it’s a safe bet that the staff of L.A. Sanitation, Hyperion Treatment Plant and Heal the Bay will be watching weather reports very, very closely.

5 p.m., Tuesday, Oct. 6: Heal the Bay Posts Action Alert

Over the last several weeks we have seen a flurry of concerning events occur in our Bay resulting from discharge at Hyperion. First and foremost on that list is the washing up of tampon applicators, hypodermic needles and other unsightly and dangerous sewage-related debris along beaches from Ballona Creek down through Manhattan Beach for several days. The most recent hypothesis from LA Sanitation is that these materials were trapped in a temporary outfall for 10 years due to a sewage overflow that happened a decade ago.

We have several concerns with officials’ explanations, especially regarding the age of the trash that washed ashore. Photo documentation as well as staff observations reveal that the debris does not show any type of algal growth or decomposition that would be expected during 10 years of sitting in an outfall pipe out at sea.

Heal the Bay will be testifying at the Regional Water Quality Control Board hearing this Thursday, Oct. 8, at 9 a.m. at the Metropolitan Water District in downtown Los Angeles. We encourage you to attend and demand that regulators hold Hyperion accountable for this failure. The amount of dangerous pollution that entered our Bay is simply unacceptable. We need answers and we need to know that this will never happen again.

More recently, the Bay has seen a major phytoplankton bloom, likely the result of the nutrients found in treated effluent flowing out to sea from the one-mile discharge pipe. The blooms are exacerbated because the nutrient loads are flowing into shallow, warm waters just a mile from shore. Fortunately, the bloom has subsided, but we may see similar blooms over the next four weeks while the main outfall pipe at Hyperion is being repaired. The bloom was recorded from Santa Monica down to Palos Verdes last week. Strong westerly winds kept it along the shoreline, rather than dispersing offshore.

None of the samples taken contained organisms of concern (such as those that are related to HABs or “harmful algal blooms”). However, there was a significant amount of shading of aquatic habitats seen during this bloom, and this reduction in visibility at the surface of the water was concerning. This shading of the water column can keep sunlight from reaching organisms that require it, such as kelp and benthic algae.

The rapid decrease of visibility in the water also didn’t match with the levels of phytoplankton that were present, suggesting that not all of the shading was just from these organisms. This adds turbidity to the list of concerns we have regarding the effluent from Hyperion and its impact on local marine life. The degradation of phytoplankton can also be oxygen intensive, creating O2 deficient waters that can be harmful to marine organisms. Fortunately, this bloom was short lived, but we will be keeping an eye on how it may have impacted our local marine ecosystems.

It has been a dramatic couple of weeks for our Bay. If you would like to express your concerns to the Regional Board, please join us this Thursday.

And please make sure to check out our Action Alert and petition demanding that Hyperion be held accountable.

5 p.m., Friday, Oct. 2: Blooms a Threat to Local Marine Ecoystems?

LA Sanitation officials continue to stress that the widespread phytoplankton blooms associated with the Hyperion discharge don’t necessarily pose a health risk to ocean-goers. But there are impacts beyond just humans. Some university-affiliated scientists who have studied the Bay for years are expressing concerns about the biological impacts of widespread and persistent nutrient loads from the Hyperion discharge.

They and Heal the Bay are especially worried about potential harm to the vibrant reef-life in the Palos Verdes peninsula area. A sustained red tide in 2005 shaded and killed all the benthic algae on the Bay side of PV Peninsula, according to Dr. Dan Pondella, the chair of Occidental College’s biology department.

Tom Ford, the executive director of the Bay Foundation and a marine ecologist, has spent years diving the PV area as part of his efforts to restore kelp stocks in the region. He emailed us these detailed thoughts:

“The dense plankton at the surface shade out the light from the kelp and other algae growing on the reefs. Putting them in perennial night, they can’t photosynthesize, so they can’t make sugars to feed their tissues, and they start to die. The plankton and the kelp compete for nutrients and, when there are high densities of plankton, they outcompete the kelp and essentially starve them.

“The plankton in the bloom are short-lived and competing with one another for food and light and they are literally dying by the trillions. When they die, they are decomposed by bacteria. The decomposition requires oxygen and the water in an area being filled with dead plankton can be stripped of oxygen by the bacterial decomposition. This lack of oxygen can lead to fish kills and the loss of invertebrates as well.

“This scenario should be one that we are concerned about, and if the bloom remains large and dense, we might see localized areas within the Bay have this process realized. The harbors, both King and Marina del Rey, have had fish die-offs in recent years, and periodically for decades, due to low dissolved oxygen and are especially sensitive to this scenario because they have limited water circulation.

“With the combination of the top two, no energy and no food, it’s not good for the kelp forest and the 700-plus species it supports. This is the same scenario at the mouth of the Mississippi, where plankton death equals low dissolved oxygen equals a dead zone. The Chesapeake Bay also suffers greatly from this same phenomenon.”

As we head into the warm weekend, there are still numerous phytoplankton blooms in our local waters. Heal the Bay staffer Jose Bacallao went on a diving trip Wednesday on the north side of PV and saw blooms in the Lunada Bay and Rocky Point region. Diving in about 70 feet of water, Jose reported that the phytoplankton was thick in the water, blocking sunlight at the surface down to a depth of about 35 feet. LA Sanitation says it will extend vessel monitoring to PV starting tomorrow and will measure turbidity and collect bacteria samples as well.

This morning Heal the Bay’s Matthew King canvassed nearly the entire stretch of plume affected shoreline, from south of the Santa Monica Pier to King Harbor in Redondo Beach. He noticed khaki green discoloration of ocean water basically across the entire coastline, with the heaviest buildup of brownish seas in the El Porto area of Manhattan Beach. Numerous surfers dotted the sea despite the bloom. As one surfer took a much-needed shower, he could be overhead cracking to his friend: “Even the wax on my board is green!”

As a reminder: Only you can decide where to swim. While these initial results indicate that recreating in bloom-affected areas at this point in time might not make you physically ill, it may be prudent to avoid these beaches. Visiting beaches that do not exhibit compromised water quality will likely provide you better enjoyment.

11:30 a.m., Thursday, Oct. 1:

Ocean users continue to send us reports of brownish and olive-green phytoplankton blooms near the shoreline, stretching in patches from Marina del Rey to as farsouth as King Harbor in Redondo Beach. LA Sanitation worked with researchers from USC to collect samples from 10 stations in the affected areas yesterday.

Early testing indicates that chlorophyll levels are elevated in the water but no harmful species have been observed at this point, according to LA Sanitation. Officials describe the geographically spread pockets of blooms to be “more ominous than harmful at this point.”

Researchers observed Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima, which is a smaller and non-toxin producing species of phytoplankton, but not the more dangerous Pseudo-nitzschia seriata. Officials expect to get further results of phytoplankton species analyses and domoic acid analyses later today or tomorrow. Researchers also said they think that the added presence of chlorine (4 parts per million) in the wastewater outflow will help knock down the phytoplankton. To balance both public health and the safety of our local marine life, Heal the Bay is keeping watch on the amount of chlorine being added to treat the wastewater. Too much chlorine is toxic to marine life – such as zooplankton, which are an important part of Santa Monica Bay’s marine ecosystem and food chain.

Although a bloom is of concern, officials say it’s not surprising or unexpected due to the discharge of nutrients (ammonia, nitrates, phosphates) with the effluent from Hyperion. Their main focus now is determining if harmful algal species are in sufficient numbers to raise concerns. They hope to have an update on HABs tonight or tomorrow.

Only you can decide where to swim. While these initial results indicate that recreating in bloom-affected areas at this point in time might not make you physically ill, it may be prudent to avoid these beaches. Visiting beaches that do not exhibit compromised water quality will likely provide you better enjoyment.

Meanwhile, there’s news on the bacterial front. Exceedances (from yesterday’s samples) have been found at the Marina Del Rey Kayak area, Santa Monica Pier, and Venice Beach at the Windward Avenue stormdrain. Again, it is wise to choose other beaches if you plan on going for a swim the next few days.

We will keep you posted when we learn more.

5 p.m., Tuesday , Sept. 29:

We continue to receive reports from eyewitnesses concerned about beach water clarity and discoloration at local beaches.

The area of phytoplankton growth that has caused discoloration of the water in South Bay beaches is still relatively small as far as blooms go in our region. Additional samples were collected today, and even more will be collected tomorrow. Once we learn more about the composition of the phytoplankton — hopefully in the next 48 hours — we can determine if it’s a harmful bloom. At this moment, there haven’t been any indicators of a harmful algal bloom, or HAB. That being said, if you go to the beach and find that there is an unpleasant odor or that the physical water quality seems unusual, use common sense. Only you can make the decision on whether or not to swim at a particular beach. And please continue to send us your photos and observations.

We are still waiting on the most recent bacterial information from beaches near the 1-mile outfall plume. The most recent sample results are from the 26th (see our update immediately below). As of now, we still recommend that beach users stay out of the water near the Redondo Beach Pier, at Topaz Avenue and at “The Box.”

6:30 p.m., Monday, Sept. 28:

All beaches that were closed due to the sewage-related trash from Playa del Rey to Manhattan Beach remain open. L.A. Sanitation tells us that daily sweeps will be conducted at these beaches to ensure that any further trash washing up ashore is handled appropriately.

The most recent set of water quality samples – taken this Saturday – do not show bacterial exceedances from monitoring sites from Playa del Rey to Manhattan Beach. However, exceedances have been found in Redondo Beach at the Pier, at Topaz and and at “The Box.” Avenue I and Herondo St. samples did not have bacterial exceedances. (Note that we are merely flagging these exceedances and cannot state that they are related to the Hyperion discharge.)

On a more distressing note, we have been receiving multiple reports today of ocean discoloration – especially in Manhattan Beach. These sightings began yesterday. We have inquired with L.A. Sanitation and they have confirmed a phytoplankton bloom, which does appear to correlate strongly with the wastewater plume from the one-mile outfall. This bloom has been seen roughly a mile from shore, from at least Ballona Creek/Marina del Rey all the way south to King Harbor in Redondo Beach.

Heal the Bay expressed concerns last month that the use of the one-mile outfall could create such blooms, as the water closer to shore is shallower, warmer and thus more conducive to phytoplankton growth as a result of the nutrient-rich wastewater.

Samples were taken in order to assess the composition of the phytoplankton and to determine if it is a harmful bloom, often known as a HAB. Just to be clear: it’s still unknown if this new bloom poses any risk to ocean users. We expect these results soon and will update as soon as we have more information.

For now, we recommend avoiding any beaches with poor weekly grades (visit the Beach Report Card site or Twitter account), any beaches with excess MOSO trash still washing ashore (please report debris to us and lifeguards if you see any), and any beaches that are foul-smelling or foul-looking. When it comes to your health, it is better to play it safe.

Last but not least, we want to extend a large thank you to our network of eyewitnesses. Our ability to protect our local beaches is strengthened when we receive information and updates from beach visitors. Over the last week we have received many concerned emails and calls. We greatly appreciate the effort and care shown in helping us heal the Bay.

1:00 p.m., Saturday, Sept. 26:

ALL BEACHES OPEN. A multi-agency task force, including L.A. City Sanitation, Beaches and Harbors, Public Health and Environmental Health, determined in a conference call this afternoon that water quality at the affected beaches is satisfactory. This decision was informed by water quality testing results, thorough sweeps and cleanups of affected beaches, surface monitoring at the site of the outfall pipe breach and the repair of the netting on the outfall pipe to prevent a breach of this magnitude from happening again.

Heal the Bay is confident that the water and beaches are safe again, but we continue to closely monitor the situation as repair on the 5-mile outfall pipe continues and we head into what could be a potent El Niño season. Again, we urge common sense precautions at all times when planning a beach trip:

- Always wait at least 3-5 days after a rain event before swimming in the ocean.

- Never swim within 100 yards on either side of a flowing stormdrain.

- Check our Beach Report Card webpage and Twitter feed for the latest beach water quality and closure information.

We’re thankful for all of your own beach reports this week: We couldn’t protect our ocean and swimmers without the vigilance and awareness of concerned citizens like you.

Remember: If you see something fishy at the beach, let us know.

9:00 a.m., Saturday, Sept. 26:

As of yesterday evening, a coalition of public health and safety agencies has decided to reopen the beach area between Grand Ave. South to 45th St. (El Segundo Beach). However, the beach area between Grand Ave. North to Ballona Creek (Dockweiler Beach) remains closed.

Please use common sense when planning a swim at any urban beach. If you see unusual amounts or types of waste materials on the sand or in the water, do not swim, alert the lifeguard and email Heal the Bay.

6:30 p.m., Friday, Sept. 25:

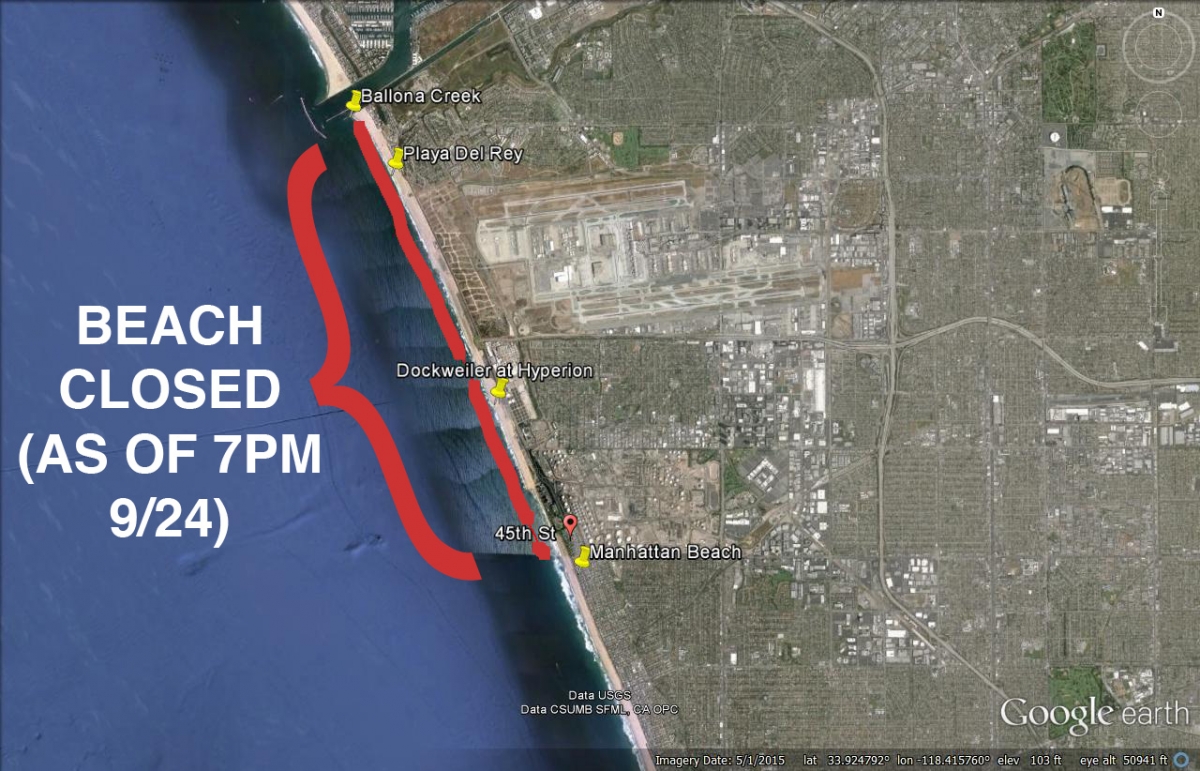

Beaches remain closed between Ballona Creek at Dockweiler Beach to 45th St. at the border of Manhattan Beach and El Segundo. However, bacterial testing of this span of coastline indicates compliance with health and safety regulations, so the Department of Public Health will use that information to determine when beaches will reopen.

Cleanup crews are continuing to clean up affected areas of coastline as needed, but most of the waste has been reported collected. However, beachgoers are reporting waste in parts of Manhattan Beach and Venice today, so the DPH has been alerted and cleanup crews activated. As always, if you see any medical or personal hygiene waste, let us know.

L.A. Sanitation and DPH are looking into redundant screening methods to supplement the newly-replaced net at the outfall point.

Heal the Bay will continue to monitor the situation and post regular updates on Twitter. You can also check the DPH’s beach advisory site here, which should have the latest information and advisories.

6:30 p.m, Thursday, Sept. 24:

Many people are concerned about reports of hypodermic needles being among the MOSO (materials of sewage origin) washing on shore at our local beaches. LA City Sanitation employee Gonzalo Barriga reported seeing 10 needles himself last night at Dockweiler Beach, along with two smaller lancets that are used for testing blood sugar levels.

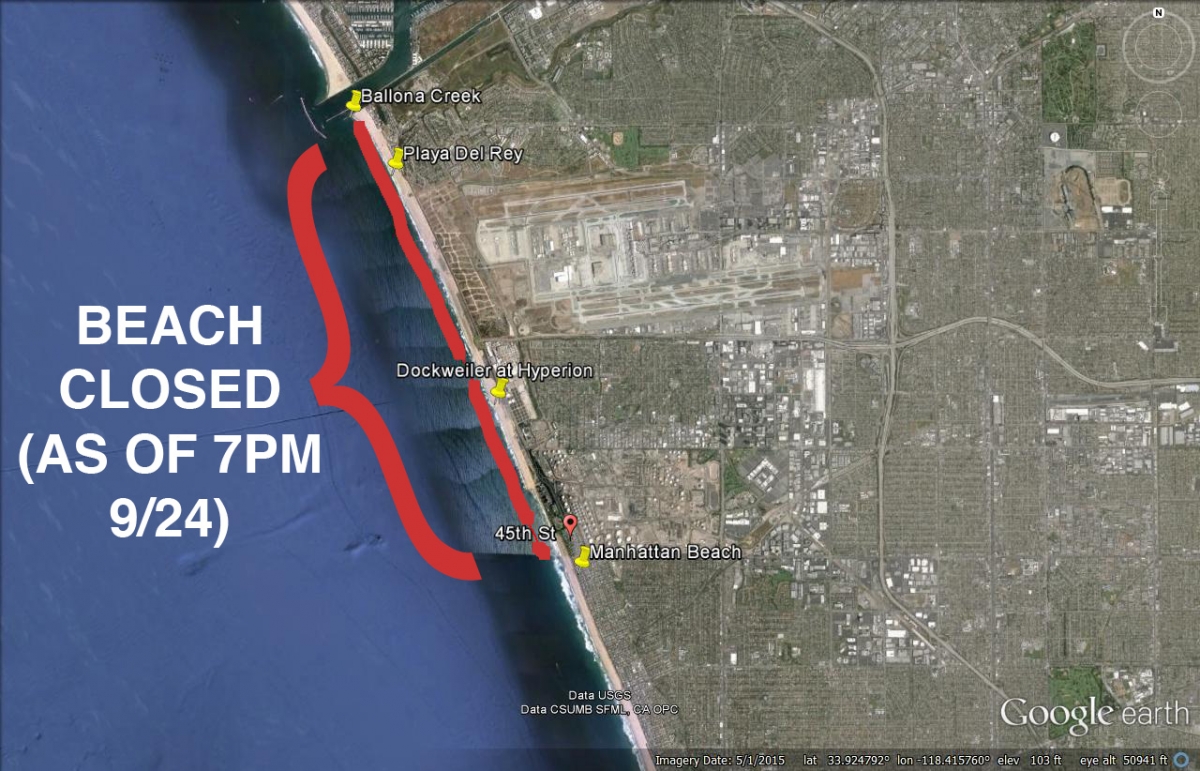

Cleanup crews all the way down to 45th Street in Manhattan Beach have confirmed finding MOSO waste, including three hypodermic needles found at 45th Street.The shoreline closure now extends from Dockweiler to 45th Street on the border of El Segundo and Manhattan Beach.

Heal the Bay has received reports from ocean users stating that they have found similar debris in the water and shorelines further south in Manhattan Beach throughout the last week. Why is waste showing up in Manhattan Beach? Probably because yesterday’s surface currents were directed south, moving the effluent plume down and parallel to the coast rather than directly onshore to Dockweiler as had been seen for the previous two days. Thus, Manhattan Beach sites may have received more trash overnight. The cleanup is ongoing.

Meanwhile, two sweeps of the initial four-mile closure areas have been completed from Ballona Creek to Grand Avenue. The area will be assessed for debris again this evening after high tide, as well as tomorrow morning.

A clean-up sweep this morning revealed that there is 80% less debris today at Dockweiler than there was yesterday, according to the LA San. Last night more than 200 pounds of material was collected. The other good news is that the latest water quality testing completed yesterday shows no bacterial exceedances at monitoring locations.

Three LA Sanitation vessels at the one-mile outfall have reported no visuals of additional trash surfacing in the last three days.

Officials stress that the MOSO material is nontoxic. However, we believe that people should avoid any stretch of beach where multiple needles and other sewage-related items have been reported in the sand until beaches are officially opened again.

So where is all this trash coming from?

Last week, Hyperion was forced to pump treated wastewater out of a backup one-mile outfall because of an emergency pump failure during the large rainfall. Unfortunately, there was no net in place at the end of the outfall to capture any of the plastic debris that came with the flow.

On Monday, when the diversion began for the long-scheduled pump repair project, a net was in place but was observed to have failed the following day. A new re-engineered net was installed today, which will hopefully help to ensure that no more of this debris is entering our Bay. The net will be checked regularly.

People have asked Heal the Bay if personal hygiene items, condoms and other types of medical trash are dumped into the sea when wastewater is discharged out of the normally used 5-mile outfall. Are we just seeing this waste on our shores now because the one-mile outfall is being employed? Is this trash normally unseen five miles out to sea?

Adel Hagekhalil, assistant director of LA San, tells us that during normal operations of the treatment plant that none of this debris should make its way through the system. His team is aggressively trying to track down the cause of the trash field, but initial reports indicated that recent heavy rains may have played a part.

When it rains heavily, much larger volumes of water than normal move through the treatment system and capture systems can be overwhelmed. Treatment plants are primarily designed to handle biodegradable solids, not plastic waste flushed down toilets by careless people. Usually, these personal items are filtered in the beginning of the treatment process, but all bets are off when heavy flows come into the plant.

And remember to check our Beach Report Card for the latest health grades for over 100 LA-area beaches, and keep emailing us with your reports and photos if you find this type of debris at your local beach.

12 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 24: Heal the Bay staff were at Dockweiler Beach early this morning to monitor the clean-up

status and speak with media about the beach closure.

Official response is still underway, with lots of City and County personnel on the beach, and clean-up crews at North Dockweiler. We also witnessed a lifeguard advising a surfer against entering the water.

We received a report from the County Dept. of Public Health this morning that clean-up crews worked through the night, removing approximately 200 pounds of tampons and hypodermic syringes from the beach. Operators at Hyperion believes this waste is likely from the wastewater treatment system becoming overwhelmed from the heavy rain last week, and flowing through the 1-mile pipe as the City began to use it for discharge of treated effluent this week during the maintenance on the 5-mile pipe and associated pumps.

Lifeguards confirmed posting closure signs at the southern end of the closure (starting at Grand Ave), and will complete posting the northern portion of the closed area at Playa del Rey to Ballona Creek this morning.

City of LA Bureau of Sanitation will also be testing the water again this morning, with results available tomorrow. Please continue to visit our running blog for updates about the closure and clean-up, as well as water quality information.

9 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 23: The County of Los Angeles’ Department of Public Health has declared an offical beach closure at Dockweiler State Beach, covering the area from Ballona Creek to Grand Ave.

The County sent the following information to Heal the Bay tonight:

“Beaches and Harbors reported tampon applicators and hypodermic needles on the beach between Culver Blvd (Ballona Creek) and Napoleon St. Current bacteria test results show bacteria levels that exceed State standards extending to Grand Ave. Therefore the closure area was extended to Grand Ave. Due to Hyperion Treatment Plant’s diversion to the 1 mile outfall, they are conducting daily sampling in the area.

According to Beaches and Harbors, Los Angeles City Department of Public Works is uncertain of the origin. They also report that LADPW and Ocean Blue, environmental clean–up contractors, are on site conducting clean-up efforts. Environmental Health Strike Team is also in route to assess the situation.

An update will be provided by 0900 Thursday 9/24/15, or earlier if pertinent information becomes available.

Los Angeles County Lifeguards have been notified to post closure signs.”

Heal the Bay will continue to monitor the situation and provide updates as we receive them.

4 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 23: This morning Heal the Bay supporters sent us photos and videos showing a concerning number of plastic tampon applicators and other sanitary trash along the high tide line at Dockweiler Beach. The eyewitnesses reported similar scenes along two miles of coastline, all the way up to Ballona Creek. City officials tell us the debris is related to last week’s big storm, which caused an emergency 200-million gallon diversion of treated wastewater out the one-mile pipe. Debris that had been trapped in the one-mile outfall pipe for some time was flushed out of the pipe and into the Bay. A good portion of debris also could have been carried by the storm overflow itself. This trash — officially known as Material of Sewage Origin — unfortunately reaches our treatment plants when sanitary and contraceptive items are flushed down the toilet instead of being placed in the trash. The Hyperion plant normally captures and removes these items, but occasionally material will wend its way through the system and be discharged to sea — especially during heavy flows after big storms. The city says it has dispatched cleanup crews to both land and sea to remove the items, which could number in the hundreds. Please let us know if you see this sort of trash at other beaches in the area.

Meanwhile, we continue to encourage people to avoid the ocean near the outfall pipe in front of Hyperion and at at the end of Imperial Avenue. Both these beaches showed bacterial exceedances above safe levels, according to water quality sampling conducted in the last 48 hours. People should not get in the water at these beaches until subseqent samples come back clean. Note: Not all beaches in the Dockweiler area have been tested, so we encourage potential visitors throughout the area to use caution.

4 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 22: Though bacterial data is not yet available, plume tracking shows the effluent reaching Dockweiler Beach late yesterday and again this afternoon. Near-outfall sampling of several water quality parameters show evidence of the plume in the top five meters of the water column but significantly diminished a half mile away. This is good news! We are now just waiting on the bacterial data to determine if it’s safe at beaches closest to the plume.

4 p.m. Monday, Sept. 21: Today marks day one of the 1-mile outfall diversion project. Today’s data show the plume of water moving up coast from the Hyperion Treatment plant and most likely reaching the shore at Dockweiler Beach this evening. Given that it’s only the first day, we don’t yet have any bacterial information but will let you know as soon as those results become available.

PROJECT FAQ’S:

PROJECT FAQ’S:

Why do they have to fix the pipe? What are they doing exactly?

In 2006 during an inspection of the five-mile outfall pipe, it was found that the “pump header”— the device that actually pumps the wastewater out through the pipe— needed to be replaced. Replacing this piece of equipment will reduce the potential for a catastrophic sewage overflow to occur at the plant as a result of a faulty pump. It’s a needed repair to ensure that Hyperion Treatment Plant continues to operate as intended.

The work will require the daily flows to be diverted to the emergency one-mile outfall, which is located much closer to the shoreline.

How long is it going to take?

The repairs are scheduled to take five weeks— starting Sept. 27 through Nov. 2 —with an additional week scheduled as a contingency plan to make sure that the newly installed equipment is correctly functioning and that the treatment plant resumes standard operations. Construction will be going on 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to try and replace the pump as fast as possible.

How much wastewater are we talking about each day?

In 2014, an average of 231 million gallons of secondary-treated wastewater was discharged to the Santa Monica Bay daily. This volume is slightly lower than the amount of sewage treated by Hyperion Treatment Plant on a daily basis, because a fraction of the treated effluent is sent to West Basin Municipal Water District for additional treatment and reuse. We hope to see more water recycling at Hyperion in the coming years to help address local water woes, while reducing effluent discharge to Santa Monica Bay.

How far is this plume of diverted wastewater going to spread? What areas are affected?

Discharging effluent out the one-mile pipeline means that it has a much higher chance of reaching the shore. With currents, winds, and waves, the effluent will eventually disperse throughout the Santa Monica Bay. Depending upon oceanographic and weather conditions, the plume will likely range from Point Dume to Palos Verdes, diluting further the farther that it travels. The predicted area with the highest impact in terms of wastewater concentration (90% probability of exposure) is from Dockweiler Beach at Imperial Highway down to Manhattan Beach.

What’s in the wastewater? What is it exactly?

Before effluent is discharged to the ocean, wastewater receives a series of physical, biological, and chemical treatments at Hyperion. This “secondary treatment” successfully removes a very large percentage of the organic matter contained in wastewater. However, the effluent still contains potential contaminants, such as metals, fecal pathogens, chemical toxins and nutrients (think food for algae and cyanobacteria), ammonia, and in this case chlorine from the disinfection process.

What is Secondary Treated Wastewater?

There are usually three treatment levels for wastewater: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Each level of treatment requires more time and resources in order to achieve a higher quality or cleanliness of water. Hyperion Treatment Plant treats its wastewater to a secondary level. This means that wastewater will have gone through both primary and secondary treatment prior to being discharged into the ocean.

Primary treatment is designed to remove large and floating solids from raw sewage. It also reduces organic material by 20%-30% and total suspended solids by some 50%-60%. Secondary treatment typically removes the remaining organic matter that escaped primary treatment. This process is then followed by having the wastewater placed in holding tanks to remove even more of the suspended solids. About 85% of the suspended solids and organic material can be removed. Finally, the wastewater goes through a disinfection process, typically with chlorine, ozone, or UV radiation, before the wastewater can be discharged into the ocean. Depending upon the disinfection utilized, there are often requirements to address the disinfectant so that it does not impact the natural environment.

Is this newly diverted wastewater dangerous or harmful? Should I be worried about getting into the water?

The city of Los Angeles designed this project to minimize negative impacts to public health, with extensive monitoring. Ongoing monitoring throughout the diversion process will tell us more about sea water quality during the diversion. Heal the Bay has asked for water quality monitoring results to be publicly disseminated as rapidly as possible, so that beachgoers can make informed decisions about which beaches to visit and which to avoid during this time. We will be keeping a close eye on the monitoring data and environmental conditions to insure that harmful algal blooms and bacteria levels remain low, and that marine life in the vicinity of the project are not impacted.

What effect could it have on local marine life?

The immediate area around the one-mile outfall has the potential to see the largest impacts, as it will be exposed to the highest concentration of effluent. Ammonia — a byproduct of the millions of gallons of urine that arrive at Hyperion every day — can be very toxic to marine life. Nutrient-rich wastewater is also a food source for algae and cyanobacteria, which can cause harmful algal blooms. Finally, the use of chlorine as a disinfectant, and its subsequent by-products, can be extremely toxic to aquatic life. As such, daily monitoring of these constituents (ammonia, nutrients, and total chlorine residual) at numerous sampling stations are very important.

Does Heal the Bay feel comfortable with what’s going on?

These repairs are needed. Without them, there is a high potential for the treatment plant to have a system failure, which could lead to a disastrous sewage spill impacting one or more of our local beaches. Hyperion is the city of Los Angeles’ largest wastewater treatment plant, and unfortunately, there is no way to stop operations and discharge completely for pipeline maintenance and maintain public health. The only option available to the city is using the one-mile outfall for the duration of the repairs. Treated secondary wastewater effluent will be pumped into shallow bay waters, not far offshore, during an unseasonably warm ocean water and potentially wet El Nino year. We are aware of the potential for this project to temporarily cause harm to marine life, increase the potential for algal blooms, and impact recreational beach waters. This is why we are so adamant about having strong monitoring, contingency, and communication plans in place.

In a time of drought, why are they dumping water into the sea anyway?

Millions of gallons of highly treated secondary wastewater flow straight from our treatment plants to the ocean every day. Unfortunately only a small percentage (about 15%) of Los Angeles’ wastewater is currently recycled due to infrastructure challenges, costs, and social misconceptions about recycled water. Given the amount of resources and policies developed to manage and obtain potable water, it is lamentable how much water is wasted through the discharge of highly treated wastewater to the ocean.

What else could we be doing with this water?

It is a goal for Heal the Bay to see treated wastewater be recycled and reused rather than flushed straight to the ocean. Heal the Bay was founded 30 years ago by fighting to improve water quality in Santa Monica Bay by cleaning up wastewater from Hyperion. Today, our focus has grown to reduce the amount of effluent discharged to the Bay through greater water recycling, which will have local water quality and supply benefits. In a city that indefinitely struggles with water sustainability and sufficiency, we envision a higher use for that treated wastewater rather than wastefully disposing of it. Recycled water, which is what you see in purple pipes, can be used for irrigation, dual-flush systems, water features, and fighting fires. Treating the wastewater to an even higher level allows it to be pumped back into local aquifers, where it can be naturally polished prior to being pumped out for consumption. Water agencies in Orange County are already recycling treated wastewater to help reduce their dependency on imported water.

How can I get more information about the ongoing status of the repairs?

If you are curious about project updates during the diversion there will be a 24/7 hotline available at (424) 259-3708. You can also call the PAO (Public Affairs Office) at (213) 978-0333 and check the SCOOS (Southern California Ocean Observing System) website for the most recent monitoring data. In addition, we will provide updates via our Beach Report Card with the most recent bacterial data from the project, as well as tweeting important information during the project.

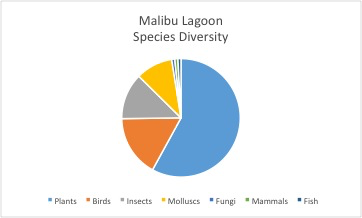

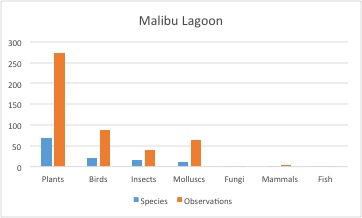

Most of our observations were of the amazing plants that rely on the wetlands to thrive. Plants form this environment’s base, providing a natural filter for water as it passes through. They also provide habitat, food, and shelter for the populations of birds, insects, and reptiles that live in wetlands. We found both sites were host to dozens of bird species including great blue herons, snowy egrets, and brown pelicans. Every year, almost one billion birds migrate along the coast of California in an area known as the Pacific coast flyway. Wetlands in Southern California are a crucial pit stop for migratory birds and the diversity of species we observed is promising. In just three hours at Ballona, we saw 17 different species of birds – almost a third of the bird species found in an extensive wetlands survey conducted by The Bay Foundation that spanned months. This shows the power of BioBlitzes to capture important data for conservation.

Most of our observations were of the amazing plants that rely on the wetlands to thrive. Plants form this environment’s base, providing a natural filter for water as it passes through. They also provide habitat, food, and shelter for the populations of birds, insects, and reptiles that live in wetlands. We found both sites were host to dozens of bird species including great blue herons, snowy egrets, and brown pelicans. Every year, almost one billion birds migrate along the coast of California in an area known as the Pacific coast flyway. Wetlands in Southern California are a crucial pit stop for migratory birds and the diversity of species we observed is promising. In just three hours at Ballona, we saw 17 different species of birds – almost a third of the bird species found in an extensive wetlands survey conducted by The Bay Foundation that spanned months. This shows the power of BioBlitzes to capture important data for conservation. From 2012 to 2013, Heal the Bay advocated for an ecological restoration of Malibu Lagoon which involved removing invasive species, replanting native ones, and adjusting the hydrology of the wetland. Inventories done by The Bay Foundation showed only six species of native plants prior to restoration, while almost 41 were noted after the restoration! Since plants form the base of an intricate web of life in the wetlands, bringing back natives can also bring back other species – including those that are threatened. At both sites our BioBlitzers found four threatened species, but that number will certainly increase with more sampling.

From 2012 to 2013, Heal the Bay advocated for an ecological restoration of Malibu Lagoon which involved removing invasive species, replanting native ones, and adjusting the hydrology of the wetland. Inventories done by The Bay Foundation showed only six species of native plants prior to restoration, while almost 41 were noted after the restoration! Since plants form the base of an intricate web of life in the wetlands, bringing back natives can also bring back other species – including those that are threatened. At both sites our BioBlitzers found four threatened species, but that number will certainly increase with more sampling.

Friends of Ballona volunteers removing iceplant from the wetlands as part of a separate initiative.

Friends of Ballona volunteers removing iceplant from the wetlands as part of a separate initiative.

PROJECT FAQ’S:

PROJECT FAQ’S: