“Large waves at the Manhattan Beach Pier draw onlookers on Saturday. The pier was closed to the public due to the high surf.” (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Waves of Waves in a Future of Climate Change

From the Desk of Meredith McCarthy, Director of Campaigns & Outreach and a Heal the Bay leader for over 20 years.

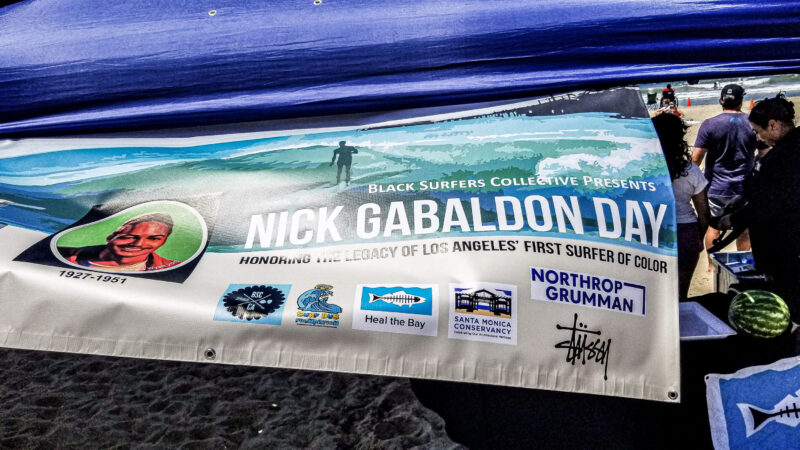

With almost macabre curiosity my boys and I head to Manhattan Beach last week to get a peek at the recent monster swell and watch the “gnarly” waves roll into Santa Monica Bay. I try to see the 10-foot sets through their eyes. The waves pound the beleaguered shoreline, a rolling thunder, an epic echo of Mother Nature’s raw power. The crunching swell is a formidable challenge for surfers struggling to paddle out. But as countless YouTube Nazare videos have shown, big waves are a challenge that can be tamed by humans.

LA Times image: A person standing on a sand berm watches as high surf breaks near Manhattan Beach on Thursday. The National Weather Service has issued high surf warnings for much of the West Coast and parts of Hawaii, describing the waves and rip currents expected to hit certain coastlines as potentially dangerous and life-threatening. (Richard Vogel / Associated Press)

I want to cling to the surfer’s narrative that these waves are gifts, a rare occurrence to be treasured. But the recent swell demonstrates that these waves are as much to be feared as cherished.

They are a preview of the future ahead of us and a reminder that a disaster can happen over decades, not just seconds. And they beg the question: can we ever really tame these waves?

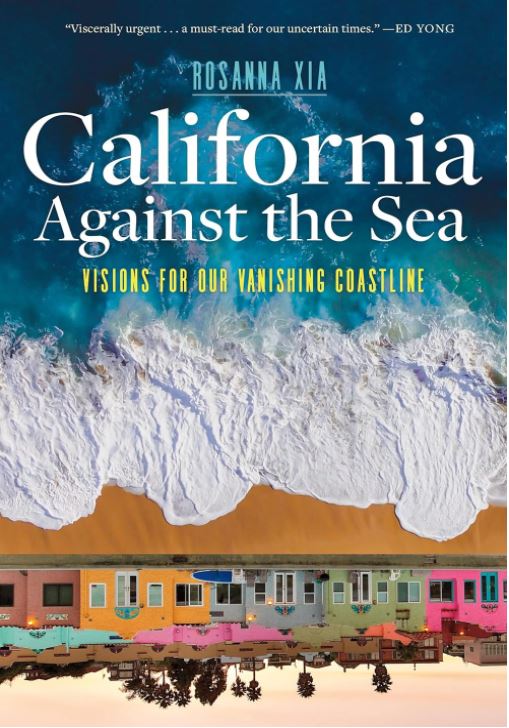

Rosanna Xia’s new book “California Against the Sea” opened my eyes as to why escalating impacts of climate change are intricately linked to the heightened severity of winter storms in the North Pacific, setting the stage for profound and harmful impacts to our beloved coast. (Purchase the book locally at Diesel Bookstore)

During my 20 years at Heal the Bay, protecting what you love has been our mantra. That mission will be harder to meet in the years to come. This recent swell is just one small harbinger of the many challenges ahead.

The connection lies in the intricate dance between climate change and the dynamics of these storms. Warmer oceans provide the necessary energy for storms to intensify, amplifying wind speeds and precipitation rates. This, in turn, translates into more powerful and potentially devastating winter storms.

The implications for coastal areas, such as Santa Monica Bay, extend beyond the immediate visual spectacle of towering waves. We all were held in awe and fear as we clicked on videos of eight people being toppled over by a rogue wave in Ventura and winding up in the hospital.

The increased storm intensity poses a dual threat: First, the potential for more severe storm surges that can inundate coastal communities, and second, the exacerbation of sea level rise. As ice continues to melt and ocean temperatures climb, sea levels rise accordingly. The cumulative effect is a compounding threat to coastal communities and the regional economies they support.

The huge surf becomes a symbol not just of the immediate dangers but of a broader trend — one that demands strategic foresight and effective management. Addressing the impacts of climate change requires a holistic approach that encompasses significant efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adaptation strategies to safeguard vulnerable coastal areas.

It can seem hopeless sometimes, but I look at my kids staring at the towering waves crashing on the sand. I wonder if they can hear the ticking of a time bomb amid the roar of the sea. I know we must act, take one small step and then bigger ones, facing this challenge head on.

Like our volunteers, the way to keep our legs under us is to rise each day in services of positive action. Our Heal the Bay volunteers are the village we rely upon to realize our mission – check out one of the opportunities below:

Become a Heal the Bay Volunteer – Orientation (Jan 11, 6p-8p): Take the first step toward helping Heal the Bay work for safe, healthy, clean coastal waters and watersheds. Come to our in-person Volunteer Orientation at Heal the Bay Aquarium.

Participate in the next King Tide’s Project on January 11 & 12, 2024, & February 9, 2024: The California King Tides Project helps us visualize future sea level by observing the highest tides of today. You can help by taking and sharing photos of the shoreline during King Tides to create a record of changes to our coast and estuaries. Observe and document King Tides on your own or join a scheduled group event.

Los Angeles King Tide Watch 2024 will be held at Manhattan Beach Pier – Jan. 12, 8:30-9:30am at Roundhouse Aquarium. Join nature enthusiasts and scientists to document the King Tide of 2024 at the base of the Manhattan Beach Pier. More information and RSVP

Join our January Beach Cleanup (Jan 20, 10 Am – 12 PM): Heal the Bay hosts cleanups every 3rd Saturday of the month (rain or shine)! This January’s storms are sure to make a mess of our beaches so kick-off your New Year’s Resolution by attending the next “Nothin’ But Sand Beach Cleanup” on January 20, 2024, at Tower 2, Zuma Beach, 10 am – 12 pm. Register today to reserve your bucket.