Heal the Bay CEO Ruskin Hartley pays a visit to one of Heal the Bay’s greatest triumphs — Ahmanson Ranch, the largest parkland acquisition in the history of the Los Angeles-Ventura County region.

The early 2000s were heady days for land conservation. Flush with funds from voter-approved bond funds, the state competed for and secured protection for some remarkable pieces of property. At the time I was working in Northern California safeguarding redwoods. Save the Redwoods League had just protected the 25,000-acre Mill Creek property at a cost of $60 million. It seemed like a lot of money at the time, but I remember hearing of two transactions in Southern California that together cost the better part of $300 million. Wow, I thought. How could anything be worth that much?

Well, this past Saturday I finally stepped foot on one of these tracts of land: the former Ahmanson Ranch (now the “Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve,” a natty name I know). In 1998, Washington Mutual acquired the Ahmanson Ranch Co. and set about developing a self-contained city (complete with two PGA golf courses) located in the rapidly urbanizing San Fernando Valley. The proposal set off a firestorm of local opposition. Locals hated the thought of all the additional traffic, and the loss of local open space that was valued by both them and the critters that called the 3,000-acre ranch home.

A textbook campaign ensued that ultimately led to the ranches protection as parkland for all to enjoy. But before it could succeed, it had to go beyond a local issue to an issue of regional and state-wide importance. And that’s where Heal the Bay came in.

Ahmanson marked the first time that Heal the Bay had played a leading role in opposing a private development, one located many miles from the coast to boot. The nexus was water quality in Santa Monica Bay and the impact that unchecked development would have on the headwaters of Malibu Creek. Heal the Bay scientists mapped red legged frog habitat, assessed downstream water quality, and mobilized regional and statewide support for what until that time had been a local issue. Ultimately the stars came into alignment and the recent passage of voter-approved park and water bonds provided the funding to halt the development and create public park land.

California Governor Gray Davis, state legislator Fran Pavley, and director-activist Rob Reiner announced the deal back in 2003. This weekend they reunited to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the acquisition.

Yes, $150 million was a lot at the time. But it truly was an investment in the future. Not only does Ahmanson Ranch protect water quality each and every day, it also provides a much needed green sanctuary in the heart of suburbia for the residents of the Valley and beyond.

It’s safe to say, that without the dogged and persistent engagement of Heal the Bay to transform a local issue to a statewide campaign, the land today would be just another subdivision and place to play golf (two rounds). And as we know, subdivisions and golf courses don’t help water quality. Quite the reverse. Society as a whole ends up paying the costs to clean up the runoff they create.

I no longer look at the $150 million as an expenditure. It really was an investment in protecting open space that has a direct return in terms of enhanced property values, forgone costs of water pollution clean-up, and the intangible values of providing people open space to recreate in. Thank you Heal the Bay!

P.S. I just read about the latest Lear Jet. For its $600 million-plus price tag you could buy four ranches (at 2003 prices). That said, you and three friends could get anywhere in the world quickly and comfortably. I will let you decide which is the better long-term investment.

Visitors enjoying the open space afforded by the Ahmanson Ranch purchase in 2003.

Visitors enjoying the open space afforded by the Ahmanson Ranch purchase in 2003.

A packed house debated the future of desalination in California at the November 13 Coastal Commission hearing.

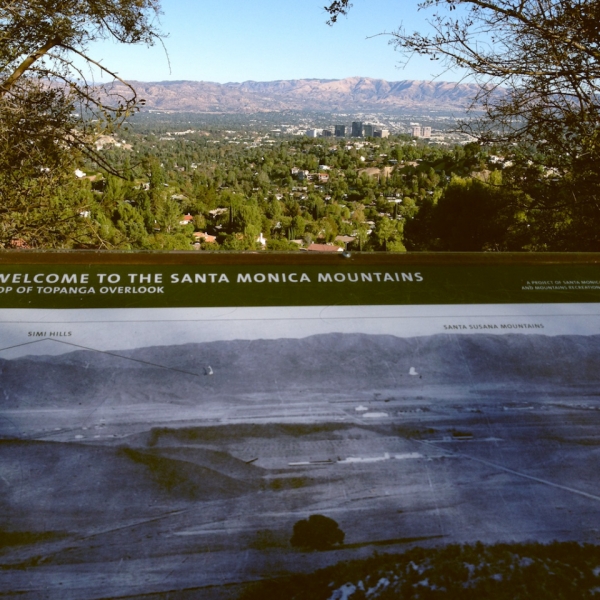

A packed house debated the future of desalination in California at the November 13 Coastal Commission hearing. Signage at the Topanga Overlook.

Signage at the Topanga Overlook. Black perch congregate in MPA off Catalina Island

Black perch congregate in MPA off Catalina Island