Local shorelines already impacted by climate change are now bracing for El Niño. The picture may not be pretty, says Heal the Bay’s Dana Murray, but there are things we can do to prepare.

What will El Niño’s footprint be on our beaches this winter? No one can say for sure, but the expected heavy precipitation and storm surges in California this winter will certainly take their toll on our local shorelines. Couple that with already rising sea levels due to climate change and the outcome could be seriously destructive and dangerous for coastal life.

Based upon historic El Niño events like 1982-83 and 1997-98, much of Southern California’s beach sand may disappear, coastal bluffs will suffer serious erosion, and some homes and businesses will flood. The suite of impacts associated with both El Niño and climate change is also a serious stressor to ocean life.

It’s important to note that El Niño is not climate change. Rather, it’s a natural cycle on Earth that occurs every 7-10 years. What remains to be seen is if our coastal ecosystems can recover and survive climate change-intensified El Niño events.

This makes strong coastal and ocean policies even more important, and Heal the Bay staff are busy advocating for such management measures. By creating marine protected areas and reducing the ocean stressors that we can control, such as pollution, inappropriate coastal development and overfishing, we are helping to buffer coastal and ocean environments from harm associated with strong El Niño events.

The eastern tropical Pacific typically averages about 10°F cooler than the western Pacific, making it more susceptible to heat-induced temperature increases, as well as creating conditions ripe for global warming to usher in Godzilla El Niños.

Scientists predict that super or “Godzilla” El Niño events will double in frequency due to climate change. This is not to say that we will have more El Niños, but rather, the chances of having extreme El Niños doubles from one every 20 years in the previous century to one every 10 years in the 21st century.

Although ocean temperatures are the common measure to evaluate El Niño intensity, sea level heights also provide an important glimpse into the strength of an El Niño. In some areas of the Pacific, particularly along the eastern side, sea levels actually rise during an El Niño. Currents displace the water along the equator, and warmer waters expand, which results in higher sea levels in the eastern Pacific and lower levels in the western Pacific. It’s important to remember that a rise of just a few inches in sea-level height can contribute to El Niño impacts.

Marine Life Impacts

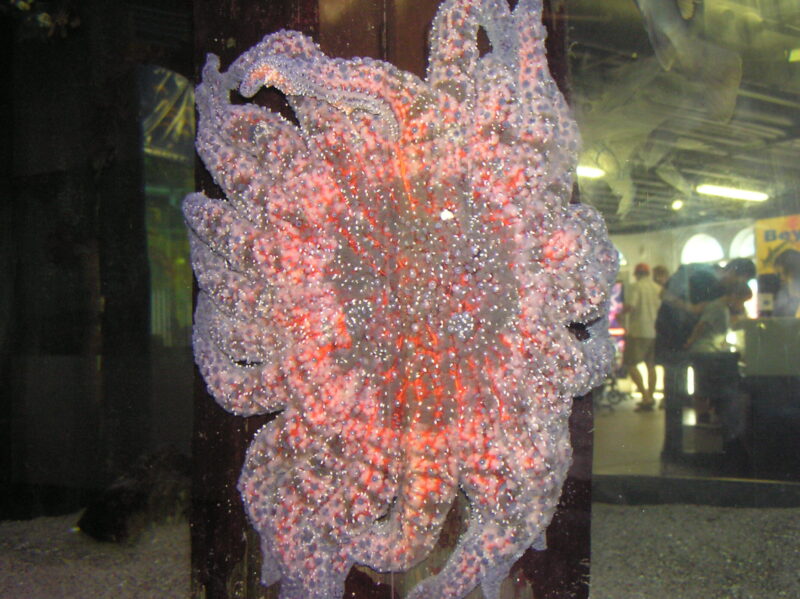

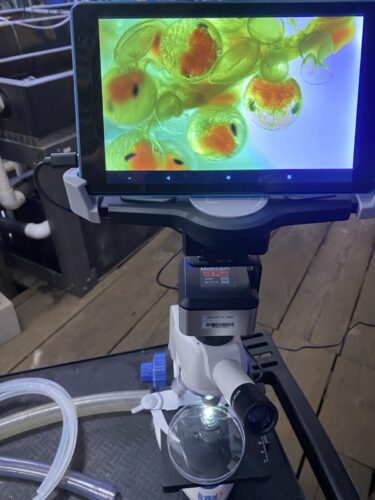

During an El Niño, marine life has to contend with stress due to extreme fluctuations in sea level, as well as warming ocean temperatures and ocean acidification due to climate change. In the tropical western Pacific, climate change will more than double the likelihood of extreme changes in sea levels that could harm coral reefs. Extreme sea level drops in the western Pacific will also last longer, putting coral under even more stress. During the 1997-98 El Niño, sea levels dropped up to a foot in the western Pacific, leaving coral reefs high and dry. 2015’s El Niño has already caused the sea level to drop seven inches in the western tropical Pacific Ocean.

Back in California, El Niño also quashes the usual upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich seawater along our coastline. The cold California current supports our oceanic food chain: from plankton and fish species, to kelp forests and marine mammals. Fish have responded to warming ocean temperatures this year by migrating north or out to sea in search of cooler waters. Consequently, sea lions have had to venture further from their young to look for those fish as their primary food source. This has had a cascading effect on California sea lion populations, leading to an unusual mortality event for sea lions this year. Following the warm ocean water, an influx of southern, more tropical marine life have moved up along California this year, such as whale sharks, pelagic red crabs, and hammerhead sharks.

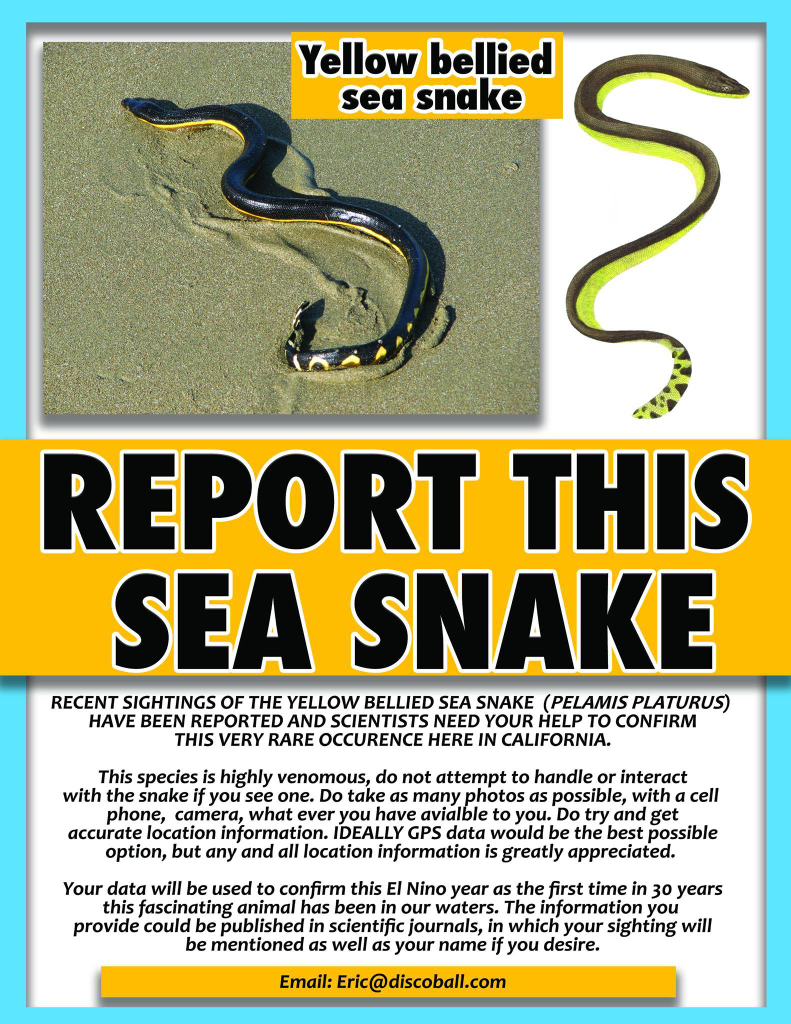

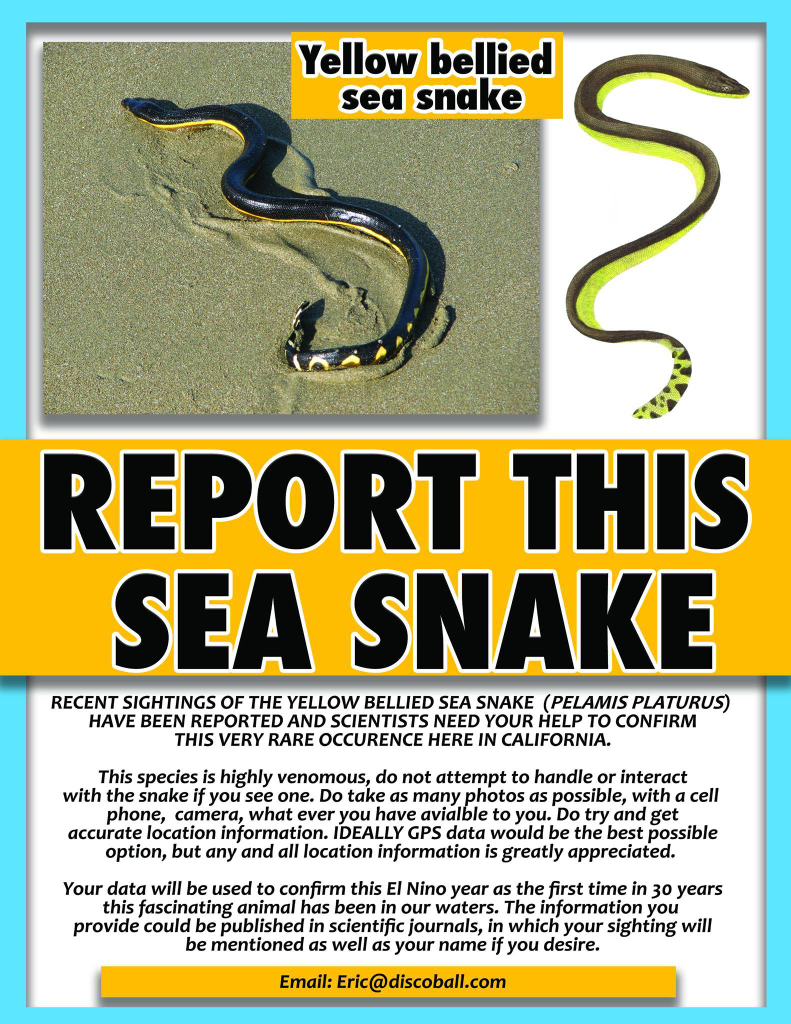

Riding the warm ocean currents across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the only sea snake that ventures completely out to sea has been spotted in Southern California waters and beaches as far north as Oxnard for the first time in 30 years. The Yellow-bellied Sea Snake has some of the most poisonous venom in the world, and is a descendant from Asian cobras and Australian tiger snakes. This sea snake is a harbinger of El Niño–it typically lives in warm tropical waters. The last time the yellow-bellied snake was spotted in California was in the early 1980’s during an El Niño. Scientists are calling for the public’s help to confirm occurrences of these sea snakes in California and your sighting could be published in scientific journals. A recent sighting took place in the Silver Strand beach area in Oxnard. As the yellow-bellied sea snake is highly venomous, the public should not handle it. Instead, take photos, note the exact location, and report any sightings in California to iNaturalist and Herp Mapper.

Shoreline Impacts

El Niño-caused sea level rise, coupled with sea levels rising from ice sheet melt associated with climate change, is projected to lead to more coastal flooding, shrinking beaches, and shoreline erosion. This year’s El Niño has western U.S. cities planning for coastal flooding. Higher sea levels, high tides and storm surges that force waves well past their usual reach pose very real threats. And when these forces coincide, such as during an El Niño, significant inundation can lay siege to coastal communities, freshwater supplies, wastewater treatment plants, power plants, and other infrastructure — not to mention public health and the environment.

El Niño-caused sea level rise, coupled with sea levels rising from ice sheet melt associated with climate change, is projected to lead to more coastal flooding, shrinking beaches, and shoreline erosion. This year’s El Niño has western U.S. cities planning for coastal flooding. Higher sea levels, high tides and storm surges that force waves well past their usual reach pose very real threats. And when these forces coincide, such as during an El Niño, significant inundation can lay siege to coastal communities, freshwater supplies, wastewater treatment plants, power plants, and other infrastructure — not to mention public health and the environment.

Locally we have several communities that are particularly susceptible to coastal flooding and erosion (photo on right shows home on Malibu beach). Venice Beach, San Pedro, and Wilmington are some of the most vulnerable local communities to flooding, according to a USC Sea Grant study examining sea level rise impacts for coastal communities in the City of Los Angeles.

Sea level rise in Los Angeles may reach 5.6 feet by 2100, which may be further exacerbated by El Niño storm events, high tides, and storm surge – especially when big wave events occur at or near seasonal peak high tides, or King Tides.

Some sandy beaches in Malibu are already eroding away with each wave that crashes on armored sea walls. Beach parking lots and playgrounds in Huntington Beach become inundated after a winter storm, as storm surges push seawater deeper into the built environment.

At Heal the Bay, we’re committed to advocating for environmentally sound climate change adaptation methods through participating in local stakeholder groups such as Adapt-LA, analyzing and commenting on proposed plans and policies, and educating the public about the coastal threats associated with climate change. We want to help everyday people understand how they can support sound solutions that protect our critical natural resources.

It’s imperative that coastal communities invest in environmentally sound adaptation solutions to be resilient in the face of climate change, especially during an El Niño year. The environmental, economic, and social impacts of sea level rise in California emphasize the importance of addressing and planning.

Preparing for El Niño and climate change requires time, money, and planning, but by investing in the long-term health of our coastal communities, we can foster resilience to coastal climate change. Protecting and restoring marine and natural coastal areas like wetlands, kelp forests, and sand dunes will leave both us and the environment better prepared and protected as we brace for the impact “Godzilla” El Niño and climate change traipsing down our beaches this winter.

A great white shark observed by Apryl in Guadalupe Island, Mexico.

A great white shark observed by Apryl in Guadalupe Island, Mexico.  Apryl speaks at EcoDive Center’s Dive Club to get the group excited for Coastal Cleanup Day, which features underwater cleanup locations in Santa Monica Bay and helps to keep the local marine habitat clean for sharks and other aquatic animals.

Apryl speaks at EcoDive Center’s Dive Club to get the group excited for Coastal Cleanup Day, which features underwater cleanup locations in Santa Monica Bay and helps to keep the local marine habitat clean for sharks and other aquatic animals. A swell shark lays eggs at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium.

A swell shark lays eggs at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium.

BACTERIAL POLLUTION

BACTERIAL POLLUTION BIG SURF

BIG SURF RIP CURRENTS

RIP CURRENTS JELLYFISH

JELLYFISH STINGRAYS

STINGRAYS SHARKS

SHARKS  SUNBURN

SUNBURN RED TIDE

RED TIDE TARBALLS

TARBALLS EATING LOCAL FISH

EATING LOCAL FISH PETTY CRIME

PETTY CRIME El Niño-caused sea level rise, coupled with sea levels rising from ice sheet melt associated with climate change, is projected to lead to more coastal flooding, shrinking beaches, and shoreline erosion. This year’s El Niño has western U.S. cities planning for coastal flooding. Higher sea levels, high tides and storm surges that force waves well past their usual reach pose very real threats. And when these forces coincide, such as during an El Niño,

El Niño-caused sea level rise, coupled with sea levels rising from ice sheet melt associated with climate change, is projected to lead to more coastal flooding, shrinking beaches, and shoreline erosion. This year’s El Niño has western U.S. cities planning for coastal flooding. Higher sea levels, high tides and storm surges that force waves well past their usual reach pose very real threats. And when these forces coincide, such as during an El Niño,