by Council for Watershed Health, Heal the Bay, Los Angeles Waterkeeper, and Randolph Consulting Group

This blog originally appeared on LAWaterKeeper.org.

Replica of Esperanza Elementary School’s Green Schoolyard created by SALT Landscape Architects, showcasing nature-based play elements

Every child deserves a school that’s safe, healthy, and allows them to thrive. In Los Angeles, a majority of LA County schools are covered in pavement. Not only does pavement contribute to high temperatures on school campuses, it also prevents water from infiltrating when LA experiences rain, leading to stormwater runoff.

Greening schoolyards by removing pavement and implementing nature-based solutions (i.e. schoolyard forests, habitat gardens, bioswales, outdoor classrooms, nature-based play areas, etc.) is one way to tackle these problems and make schoolyards safer and healthier for students. Implementing schoolyard greening projects in Los Angeles has proved challenging.

Council for Watershed Health, Heal the Bay, Los Angeles Waterkeeper, and Randolph Consulting Group have teamed up to promote large-scale schoolyard greening and stormwater management throughout LA County, particularly in LA’s most park-poor and historically impacted communities.

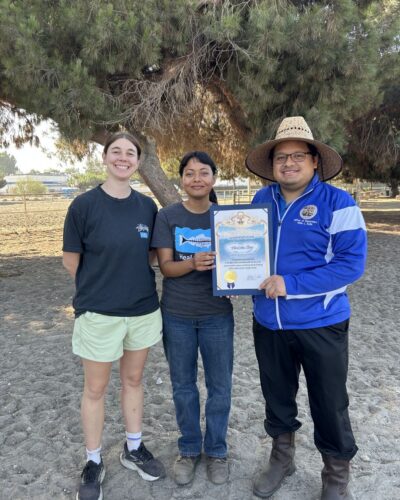

Annelisa Moe (Heal the Bay), Alejandro Fabian (TreePeople), and Ben Harris (LA Waterkeeper) at the Managing Stormwater on School Campuses: From Potential to Permits session at the Green CA Schools Summit in Pasadena

Our team launched our partnership with a session at the Green CA Schools and Higher Education Summit in Pasadena on November 13, 2025. The Summit opened with remarks from State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tony Thurmond, and Deputy Superintendent, Abel Guillen, as well remarks from the Mayor of Pasadena, the SoCal firestorms still fresh on the speaker’s mind, they spoke about resiliency and the role schools play in supporting more climate resilient solutions, increasing shade canopy through trees, greening of school campuses and the importance of teaching stewardship to students. It was great to see these points elevated by state leadership.

Los Angeles County is in a unique position to lead in the state because of the L.A. County’s Safe Clean Water Program, which funds stormwater projects to improve water quality, increase water supply, and provide community benefits. Schools are a critical component of this ecosystem by managing stormwater and greening campuses, we increase climate resiliency, and provide an enriched learning environment for students across the region. The more we are able to connect greening and stormwater management, the better for the region.

The session we put together, titled Managing Stormwater on School Campuses: From Potential to Permits, walked attendees through what stormwater runoff is and the impact of stormwater pollution on our waterways, data from a TreePeople study on the potential of LAUSD schools to contribute to stormwater management, and the regulatory environment for stormwater management (i.e. are you now or will you be legally required to manage stormwater).

The key takeaways we wanted the audience to leave with are:

- In LA County, the average one-inch rainstorm results in 10 billion gallons (30,700 acre-feet) of runoff moving through the storm drain system.

- Looking at all schools in LA County, there is a total of 19.5 billion gallons per year (60,000 acre-feet/yr) of stormwater management potential (this volume would address almost 75% of LA County’s groundwater recharge goal for context), and strategically selecting the sites with the greatest potential, 10% of the sites (78 LAUSD sites) could achieve 9.8 billion gallons per year (30,000 acre-feet/year).

- While schools are not currently regulated by a stormwater permit (i.e. required to legally manage their stormwater), they are one of the few entities left that are not regulated and are likely to be regulated in the future.

Overall, we are galvanized by the momentum that is building in Los Angeles for green schoolyards and will be hosting our own symposium in May exploring the many synergies of school greening and stormwater. We look forward to seeing you in May.

Want more schools and stormwater content?

Have ideas for stormwater management projects in your community?

Submit ideas to the SCWP Community Strengths and Needs Assessment.

This work is supported by Water Foundation and the Los Angeles County Flood Control District’s Safe Clean Water Public Education and Community Engagement Grants Program